Manufacturing the Doctor of Letters: In the footsteps of Camille Jullian

1. A degree without a curriculum

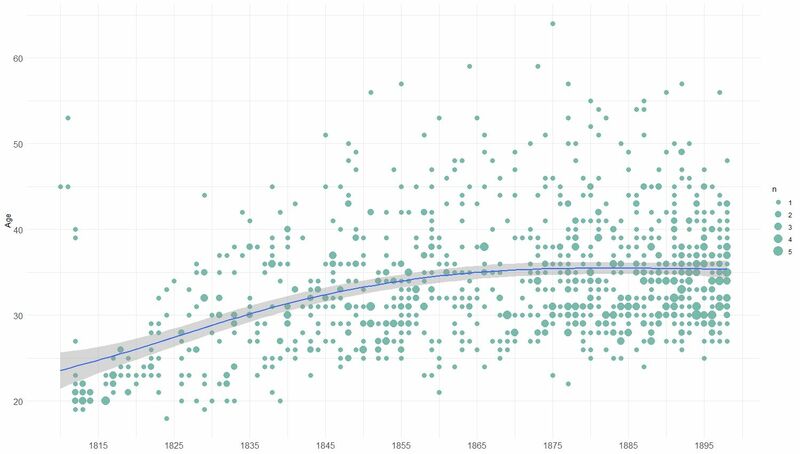

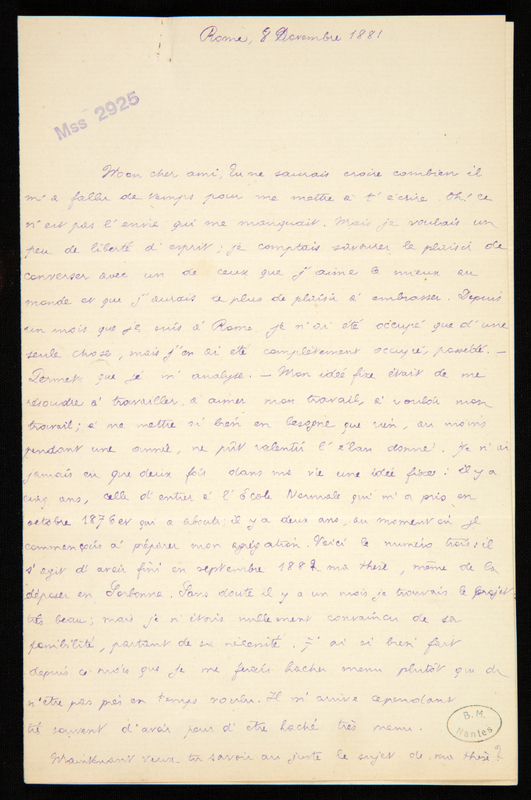

The case of Camille Jullian provides a particularly rich guiding thread for examining the career of a “doctoral student” in the nineteenth century. This is due to the availability of his correspondence, which has been collected and studied by Olivier Motte. Born in Marseille on March 15, 1859, the young Jullian entered the École normale supérieure in 1877. There, he followed the lessons of Numa Fustel de Coulanges, Ernest Lavisse, Gaston Boissier, Gabriel Monod and Ernest Desjardin. In 1880, he was admitted to the Agrégation in History, ranked first, and was promptly dispatched to the École française de Rome, founded five years earlier to encourage historical research on Italy. He then began to prepare his doctoral thesis with the aim of obtaining a position as a maître de conférences quickly, thus avoiding teaching in a lycée – as was standard until then, before the introduction of the maître de conférences positions in 1877 offered an alternative. The preparation of the doctorate is carried out without any specific administrative framework, without prescribed curriculum, without a thesis supervisor or advisor – a function that only appears officially for the Doctorate of Letters with article 3 of the decree of June 16, 1969. It is notable that the founding decrees and subsequent regulations were only devoted to the defense, as an examination, but did not provide anything for its preparation. Not even a minimum or maximum time interval between the bachelor’s degree and the doctorate was stipulated. In the absence of annual administrative registrations, which would have conferred student status and left archival traces, the tendency to increase the time needed to produce acceptable theses can only be measured indirectly, by the age of the candidates [fig. 1]. However, what is most striking is the very wide dispersion of this age, a consequence of the absence, or near absence, of a conventional, organized trajectory leading to the doctorate. In the absence of any formalized training system, each candidate arrived at the doctorate by his or her own idiosyncratic way.

In the absence of any legal obligation to the faculty, candidates were similarly not subject to any legal duty: they were given the greatest freedom, which allowed the majority to prepare their theses by teaching in secondary education, while a minority like Jullian took advantage of the mechanisms set up by the Third Republic – French institutes abroad, like the Ecole française d’Athènes or the Ecole française de Rome, ministerial missions in Germany or the United Kingdom, etc.

2. Early Roman trial and error

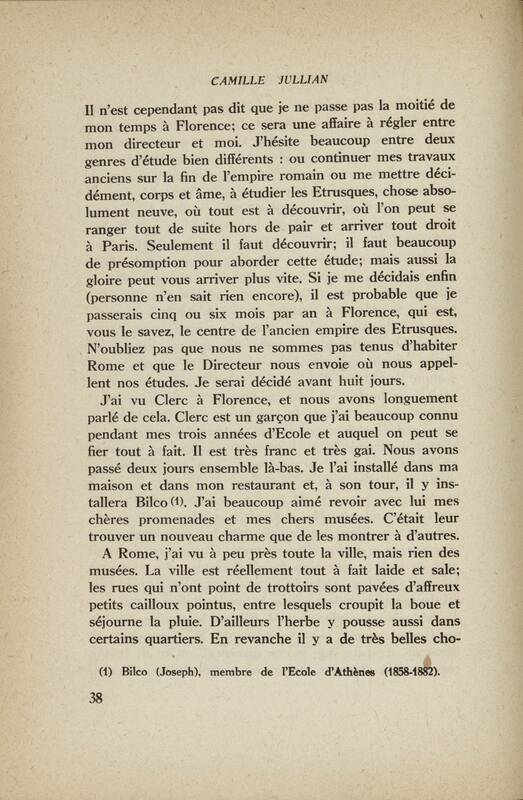

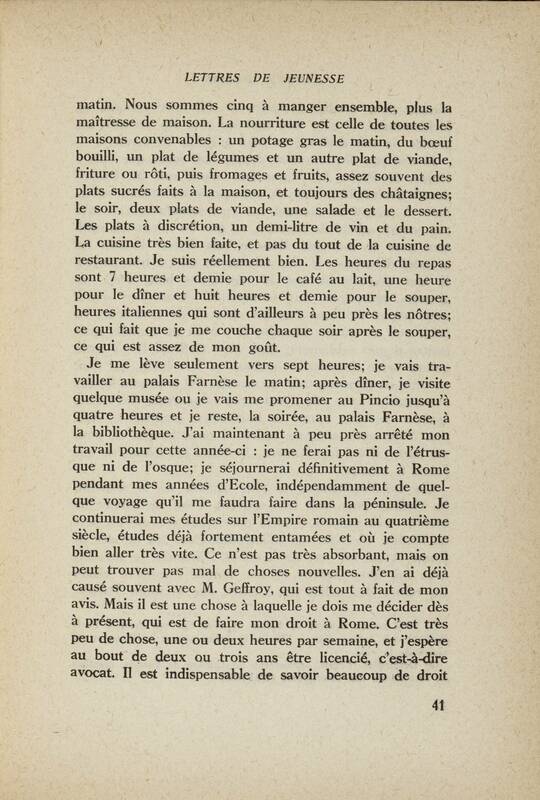

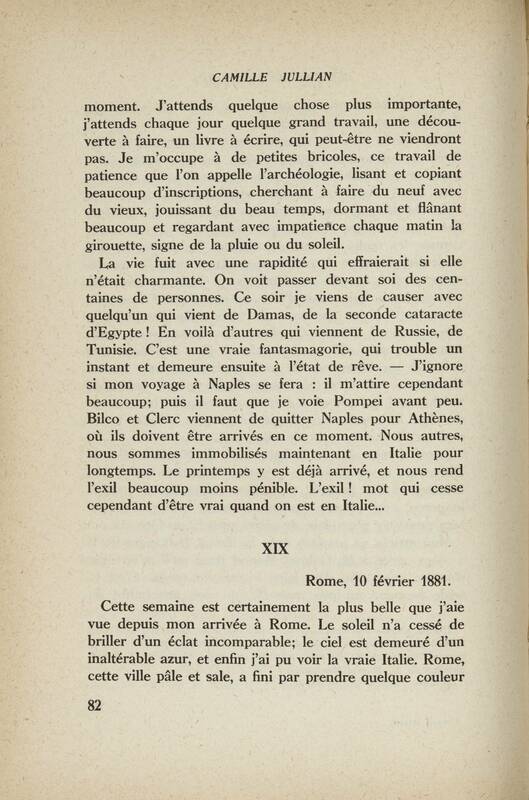

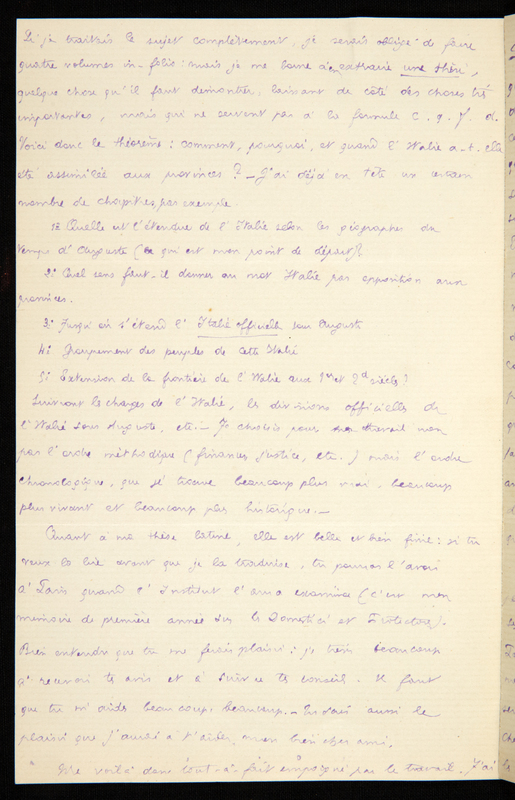

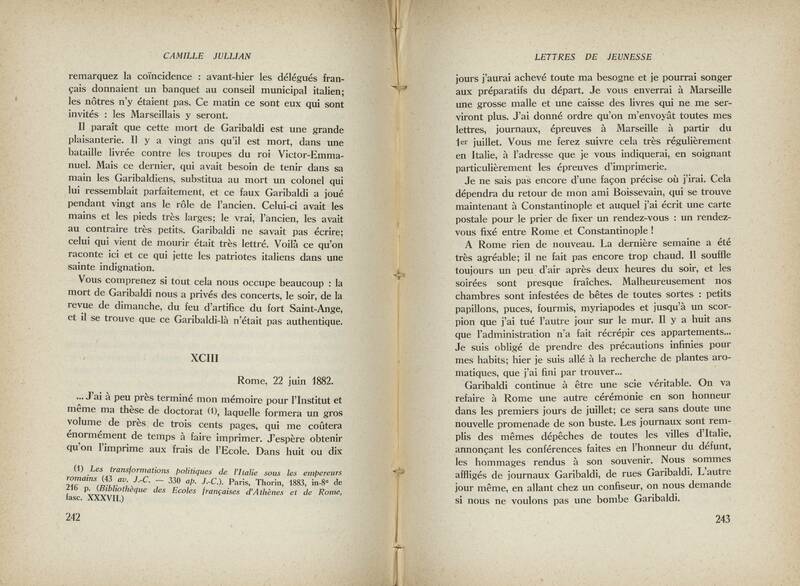

Jullian was free to commence construction of his theses in Italy, with the preliminary, unofficial project of investigating the Roman landed aristocracy in the fourth century BCE. The correspondence with his teachers and peers, which began the day after the agrégation, permits a detailed examination of the discussions surrounding these theses. As soon as he arrived in Rome, Jullian was immediately drawn to the study of Etruscan history and language [Fig.2 and 3] (to the extent that he considered pursuing the agrégation in grammar). He subsequently shifted his focus to the early days of Christianity, and then returned to the fourth century [fig. 3] through the study of imperial institutions. This shift in focus is evident in a letter he wrote to Fustel de Coulanges on December 22, 1880. This choice was mainly motivated by the desire to speed up his career progression by achieving results rapidly. The document upon which he based his thesis, the Notitia Dignitatum, was included in the agrégation program at the time he undertook it. However, the subject failed to inspire him, and he worked without conviction [fig. 4]. In a letter to his comrade, Alfred Rebelliau dated November 8, 1881, he announced that he had set himself the goal of completing his theses by September 1882 [fig. 5]. He planned to devote the French thesis to the administration of Italy, from Augustus to Aurelian, in order to analyse the Notitia as well as possible, rewriting the history of the administrative division of Italy by doing so. Additionally, this subject was explicitly chosen as a means of challenging the interpretations of German historiography in general, and those of Theodor Mommsen in particular. Meanwhile, Jullian sought the patronage of Fustel de Coulanges [fig. 6]. As for the Latin thesis, he chose to translate another text, which he had to write anyway: the Ecole française de Rome required of its members a dissertation, which had to be sent to the Académie des inscription et belles lettres, the institution in charge of overseeing it. Jullian’s dissertation was dedicated to the Protectores Augusti, the imperial guard. Such recycling was then frequent among the students of the institutes of Rome and Athens: the French thesis defended by Paul Vidal de la Blache in 1872 on Herodes Atticus, for example, had the same origin.

3. Registration at the Sorbonne... and departure for Berlin

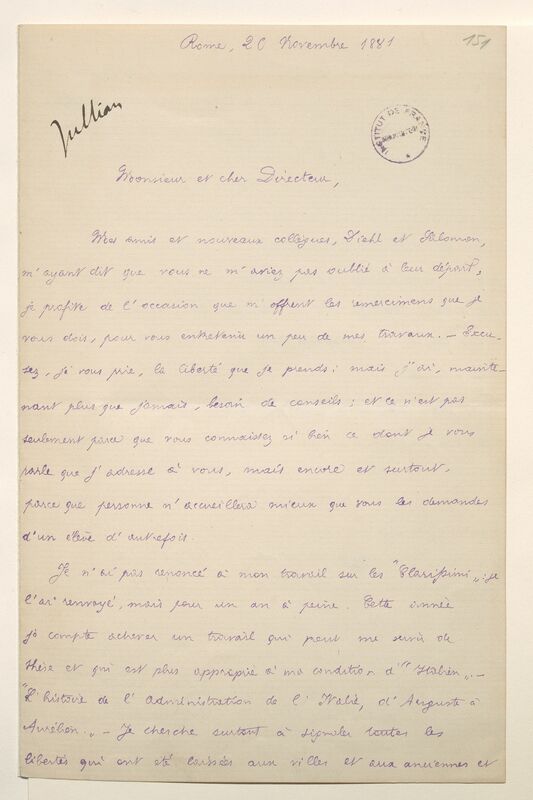

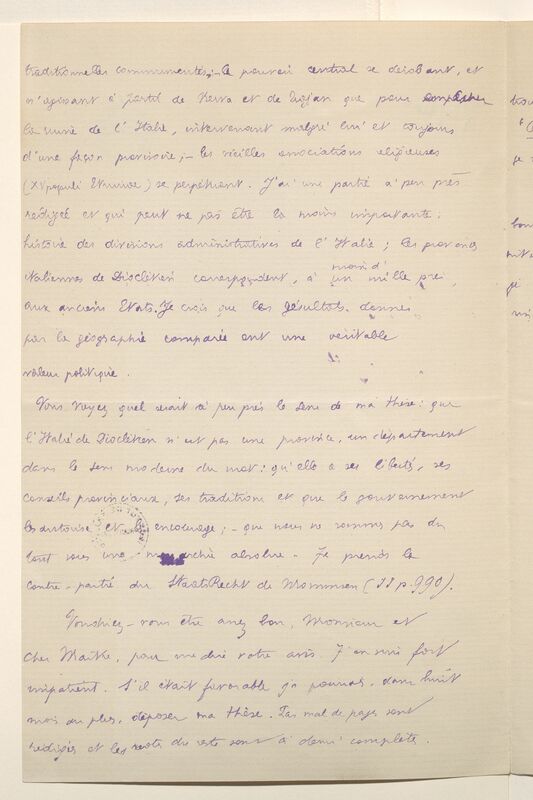

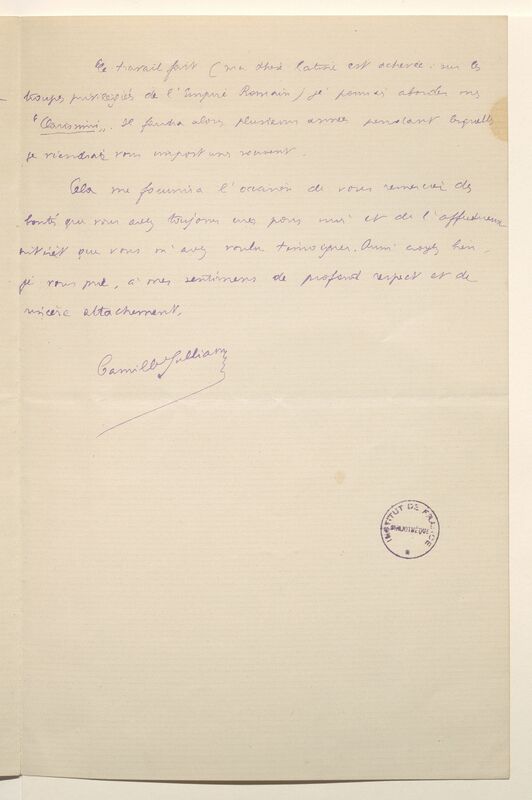

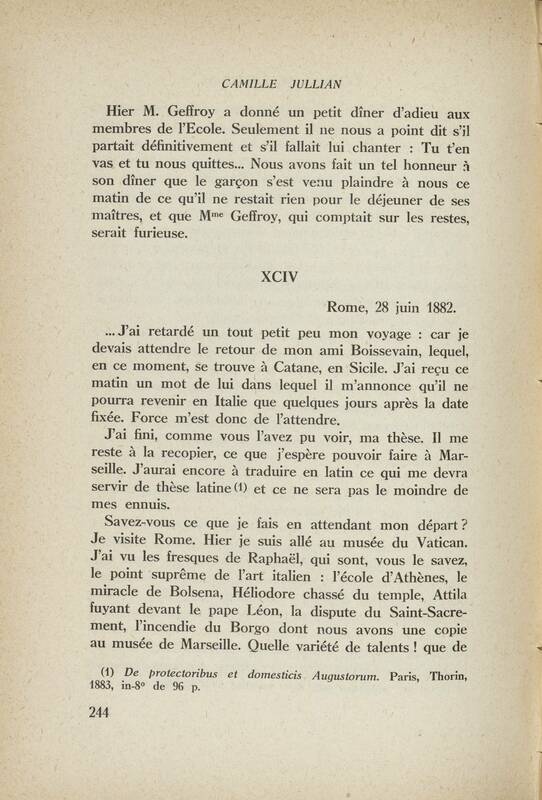

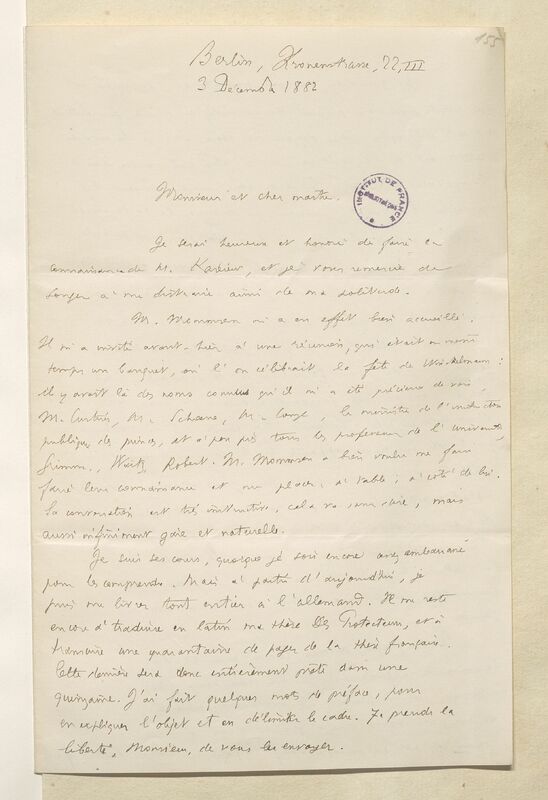

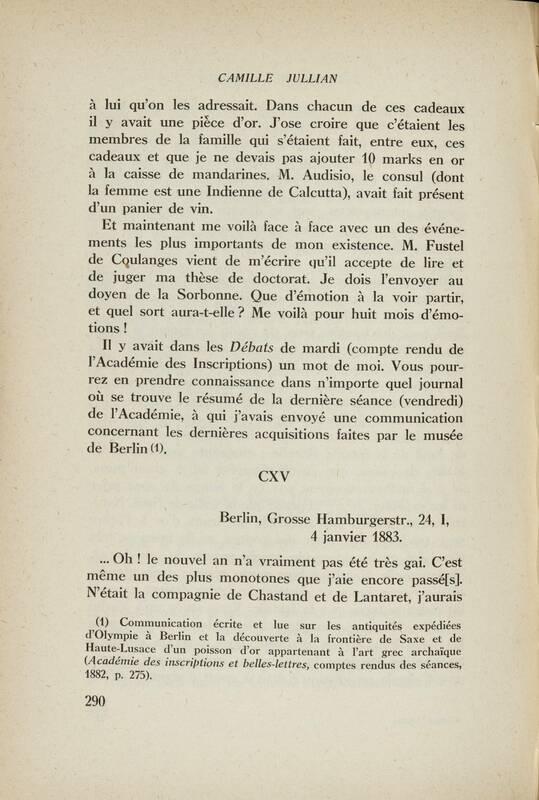

The concrete manifestation of this decision at the Sorbonne, the degree-awarding institution, was minimal. On January 7, 1882, the director of the École française de Rome, Auguste Geffroy, simply informed the dean of the Sorbonne, Himly, of the subject; Himly unofficially took note of it, to prevent two candidates from unknowingly working on the same subject. From that point onward, Jullian devoted himself exclusively to his subject: at the end of June 1882, he announced to his family that he had finished writing [Figs. 7 and 8], and the memoir was duly submitted to the Académie. In reality, he was not satisfied, as he told Rébelliau in a letter dated July 27, 1882: “I have finished my thesis, but it will have to be rewritten”. Rather than spend a third year at the École française de Rome, in the spring of 1882 he requested to be released from his studies to undertake a mission to Berlin on a mission from the Ministry of Public Instruction. This involved attending courses in Roman law, epigraphy, and philology, particularly those of Theodor Mommsen and Ernst Hübner. Upon his arrival in October 1882, Jullian initially dedicated his time to resuming his thesis, tidying up his drafts, completing the manuscript of the French thesis of 200 pages in December. He translated his Latin thesis of 150 pages in one month, in January 1883.

4. Defending

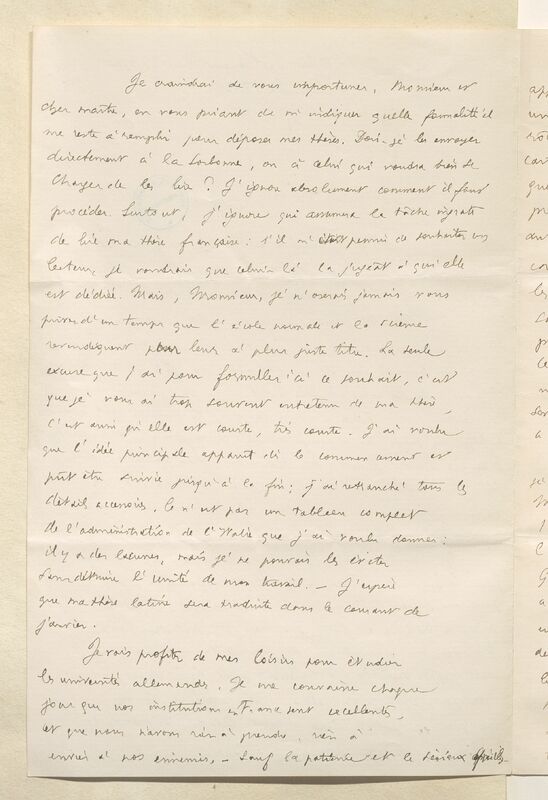

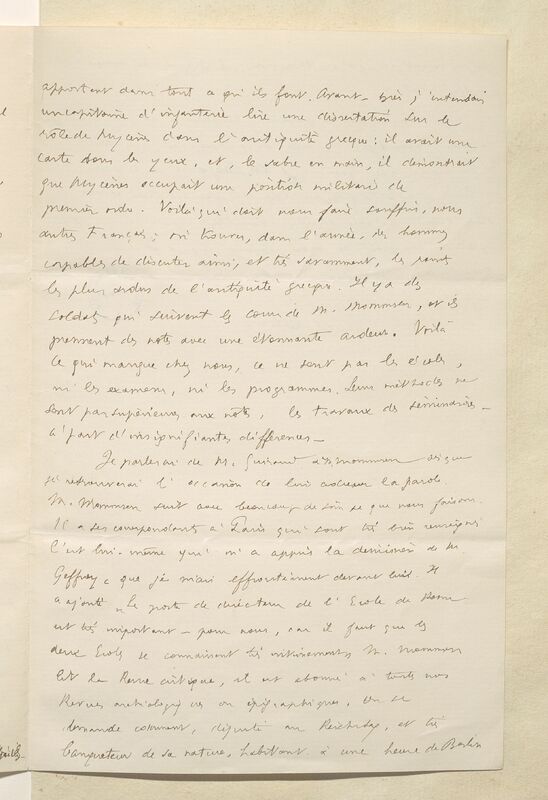

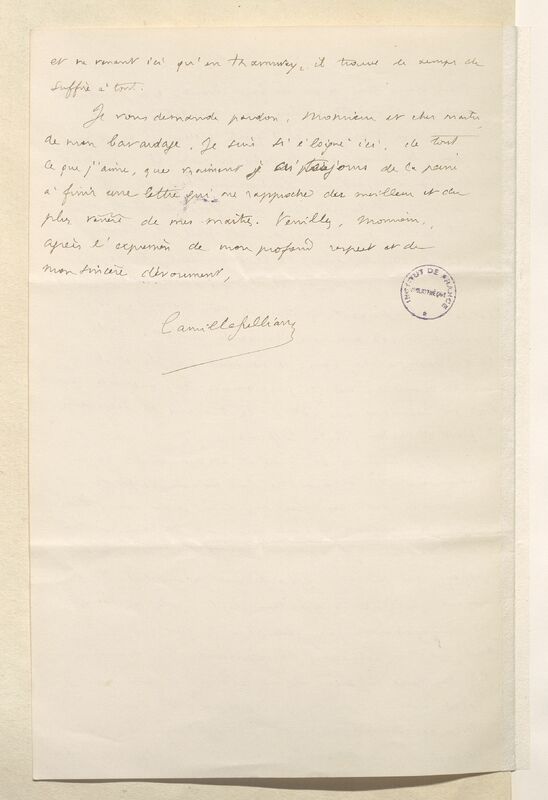

It was only then that Jullian began to consider the administrative dimension, admitting – more or less candidly – in a letter to Fustel de Coulanges, dated December 3, 1882, that he “absolutely did not know how to proceed” [fig. 9]. The procedure for doctoral theses was apparently simple: first, the candidate submitted the two theses to the dean, who appointed a rapporteur for each, from among the professors of the faculty; then the rapporteurs were tasked with writing a report, indicating whether or not the defense should take place. The appointment of the rapporteur is therefore crucial, and the candidate could only hope to exert indirect influence over the choice. This may be achieved through the dedication, for example, in the hope that it will consciously or unconsciously guide the decanal choice. Alternatively, the candidate may hope that his possible supporters and mentors would informally propose to the dean that they assume responsibility for the task. This was undoubtedly Jullian’s objective with this subtle letter to Fustel de Coulanges. The same process occurred concurrently with the Latin thesis, which was entrusted to another rapporteur, in this case Geffroy. The thesis was dedicated to Ernest Desjardins, a recognized authority in historical geography and epigraphist, but Desjardins, a lecturer at the École Normale Supérieure, did not have the status that would allow him to write the report: it had to be authored by a faculty professor. It was evidently crucial to make informal contact with the likely referees beforehand, to ensure that the thesis would not be officially rejected by the dean or the rapporteur. If it was still possible to resubmit it, the procedure was so lengthy (Jullian estimated that it would take eight months) that failure was very costly [Fig. 10].

Fustel sent his observations to Jullian at the end of January.

The dean, having received the professor’s favourable assessment, affixed his “visa” to the manuscript, i.e., he certified that he had read it, and that the thesis could be defended, thereby assuming responsibility on behalf of the faculty – the report was, in theory, only advisory. Once the visa has been affixed, the thesis was sent to the rector, who represented the administrative and ministerial power, who is responsible for issuing it with the printing permit (or “imprimatur”). At the time of Jullian’s defense, the decree of July 30, 1883 had just introduced a theoretical counter-power to the rector’s action: if the imprimatur was refused, the faculty or the candidate could henceforth request the constitution of a special commission by the minister, whose role was to provide an opinion on the subject of the theses.

Those operations of academic and institutional validation did not suppose, in fact, that the text was completely fixed: the manuscript was sent back to Jullian, who integrated Fustel’s remarks before sending the revised version to the publisher [fig. 11]. The publisher was Ernest Thorin, and the École française de Rome agreed to cover the printing costs of the French thesis, which resulted in the volume being designated fascicle 37 of the Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d’Athènes et de Rome. Since the printing was done in Toulouse while Jullian was still in Berlin, the proofreading process was lengthy and complex: three successive sets of proofs were corrected, and the two books were not finalized until the beginning of August 1883.

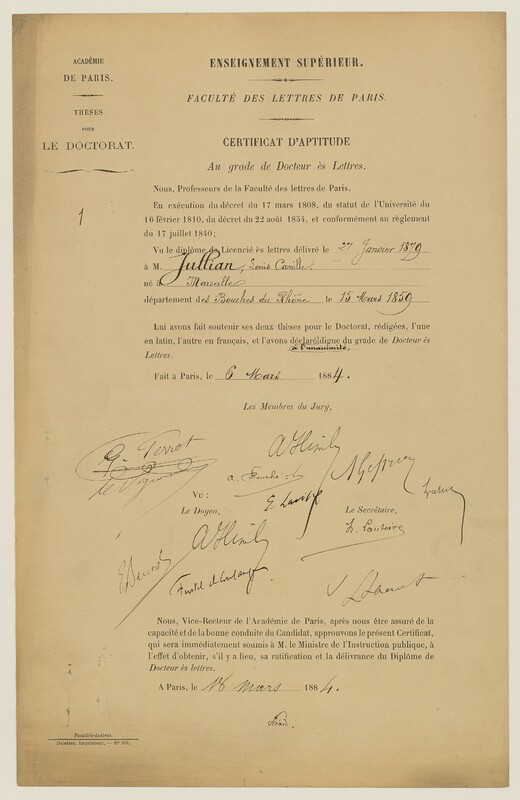

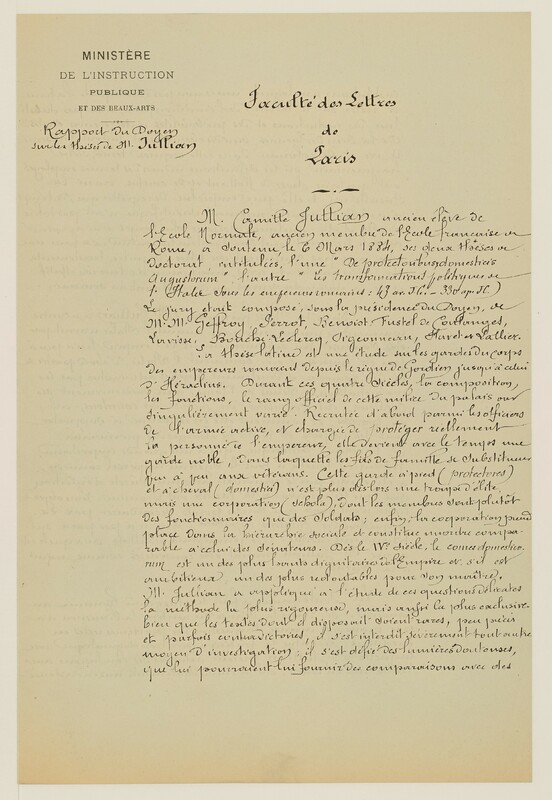

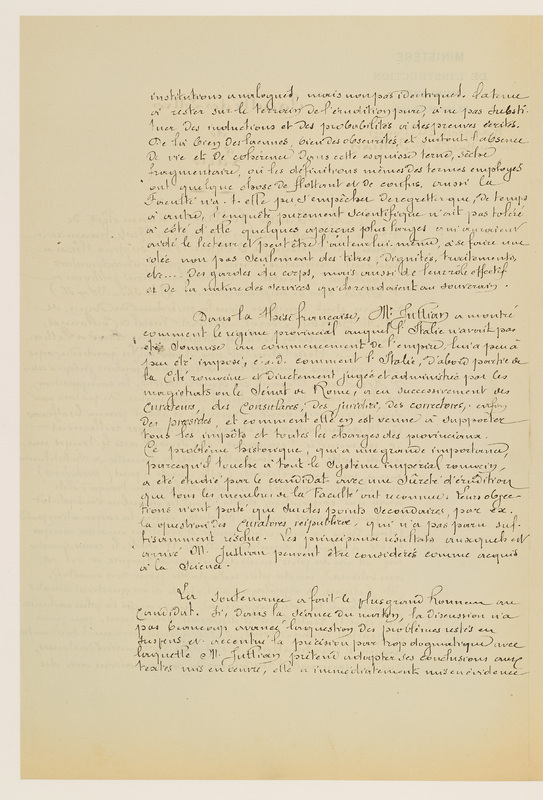

On his return from Germany, Jullian was appointed, by decree of October 11, 1883, as a maître de conférences at the Faculty of Letters in Bordeaux. But he wasn’t a doctor yet: the defense did not take place until March 6, 1884, the large number of candidates constantly postponing the defense. The jury was composed of Himly, dean of the Faculty of Letters in Paris, the rapporteurs Geffroy and Fustel de Coulanges, as well as Auguste Bouché-Leclercq, Henri Pigeonneau and Roger Lallier. Georges Perrot, Eugène Benoist, Ernest Lavisse, and Ernest Havet seem to have been present but to have taken little part in the debates, as evidenced by their absence from the reports. As was a common occurrence in the latter part of the century, Camille Jullian’s defense attracted the attention of journalists, resulting in comprehensive articles in La Revue critique d’histoire et de littérature, which gave an almost verbatim account of the debates, and the Revue de l’enseignement secondaire et de l’enseignement supérieur. The defenses at the Sorbonne had in fact become long-term shows: they generally lasted six hours. For each thesis, after the dean’s speech, the rapporteur and then the other members of the jury spoke and argued with the candidate – this was a novelty of the Third Republic, as previously the professors argued in simple order of seniority, leaving little time for the youngest, even though they might have been the most competent on the subject.

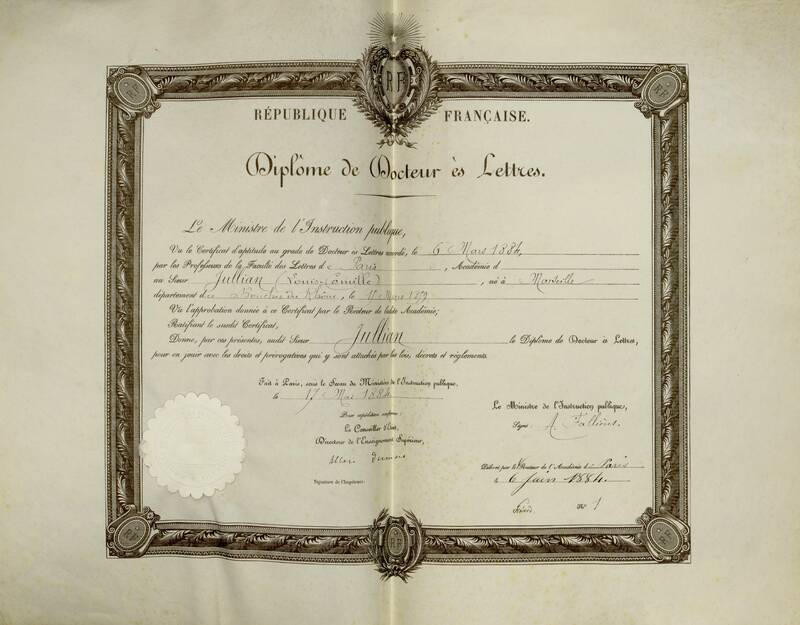

At the end of the defense, the jury awarded the candidate a certificate of aptitude for the degree [fig. 12], declaring him “worthy of the degree” of doctor. This document was then sent to the Rector, who, in turn, appended his signature, adding that he had “ascertained the candidate’s ability and good conduct” – a step that has become formal since the middle of the century. The certificate was then transmitted to the minister (in practive to his services, in particular to the direction de l’enseignement supérieur), who ratified it and officially issued the diploma [fig. 13] – for the sum of 140 francs. As a matter of fact, from a legal point of view, it was not the faculty that legally awarded the doctorate, but the minister himself.

Since 1840, this certificate has been accompanied throughout the administrative process by the dean’s written report on the defense. From the Second Empire onward, an academy inspector present in the room also provided a written account of the defense. These two documents were usually added to the candidate’s file and provided guidance to the administration in its career management. Dean Himly [fig. 14], after summarizing Jullian’s Latin thesis, emphasized in this case the erudition of the candidate, his use of “the most rigorous but also the most exclusive method”, which contrasts with the more literary practices of the dean’s generation, leading him to criticize “the lack of life and coherence of this dull, dry, fragmentary sketch”. On the contrary, during the defense, Fustel de Coulanges praised the candidate for having “not a sentence of declamation, not a subjective judgment”. Nevertheless, the dean’s assessment of the French thesis was much more lenient: “the main results obtained by M. Jullian can be considered as acquired by Science”. Above all, in his eyes, it was the defense that “did the candidate the greatest honour”: he underlined “the certainty of his memory, the surety of his words and his in-depth knowledge of the documents”. Jullian was thus “unanimously declared worthy” of the degree of doctor, which was the highest honour before the introduction of distinctions (mentions) in 1894.

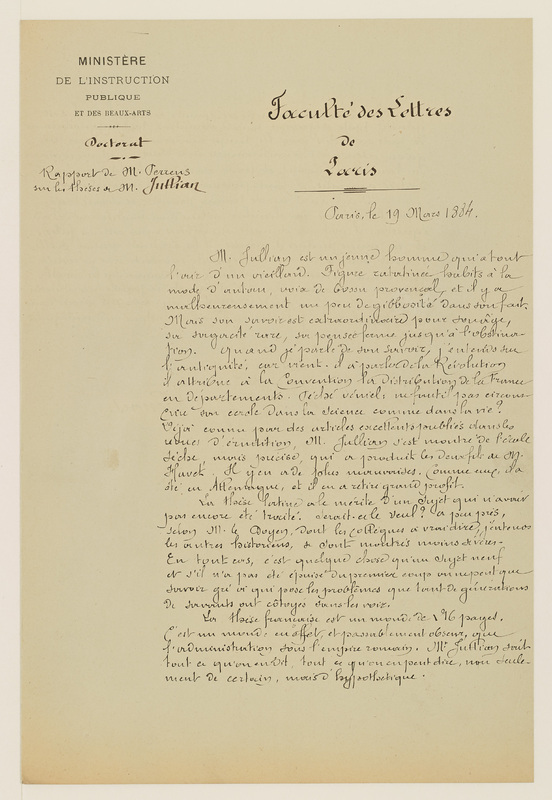

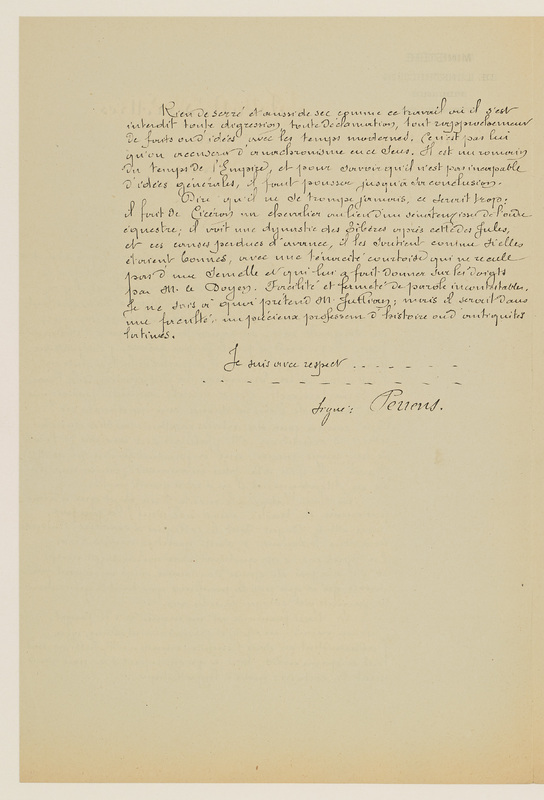

The report written by Inspector François-Tommy Perrens [fig. 15] shows the extent to which these unofficial reports were intended to supplement, nuance, and, if necessary, counterbalance the assessments of the deans (it must be noted that the inspectors had read the deans’ report at the time they wrote their own), and to further refine the social technology for guidance and management of doctors’ careers by the central administration. The reports were even more direct than the decanal texts, and they frequently began with a physical description of the candidate. These descriptions were often cruel, as is the case with Jullian, quickly described as follows: “shrivelled face, clothes in the fashion of yesteryear, voice of a Provençal hunchback”. This physical portrait served as an introduction to a moral and intellectual portrait of the candidates: “his knowledge is extraordinary for his age, his sagacity rare, and his thought firm to the point of stubbornness”. As the dean, he emphasized the candidate’s “dry but precise” erudition, while stressing that there are “worse” schools of scholarship. He mitigated the dean’s criticism by recalling that the subject of the Latin thesis was new, which was at least “something”, and defended the richness of the French thesis, “a world of 216 pages”. Here again, the behaviour displayed during the defense was of great importance, as it revealed the academic ethos of the candidate, capable even of making up for factual errors: “these lost causes, he supports them as if they were good, with a courteous tenacity that is unwavering; a quality that has led the dean to give him a rap on the knuckles. Lightness and firmness of speech are unquestionable. I do not know what M. Jullian pretensions are; but he would be a valuable professor of history or Latin antiquities in a faculty”.

It is undeniable that "M. Jullian" had high pretensions: when Ernest Desjardins, who had recently been appointed to succeed Léon Renier in the chair of epigraphy and Roman institutions at the Collège de France, died suddenly on October 27, 1886, he was in line to succeed him, at the age of 27. However, René Cagnat ultimately secured the position. In 1891, Jullian was appointed professor of the history of Bordeaux and Southwest France, and in 1905 he left Bordeaux to take up the chair of national antiquities at the Collège de France, finally fulfilling the goal he had set for himself at the École normale supérieure.