Doctors of Letters in the Nineteenth Century: Some Portraits

1. Pierre Fontanier, the first Doctor of Letters

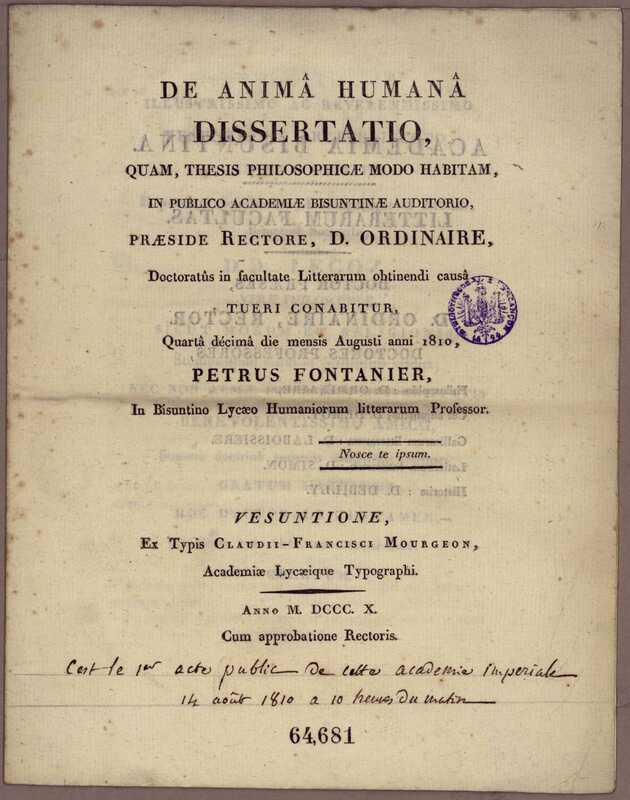

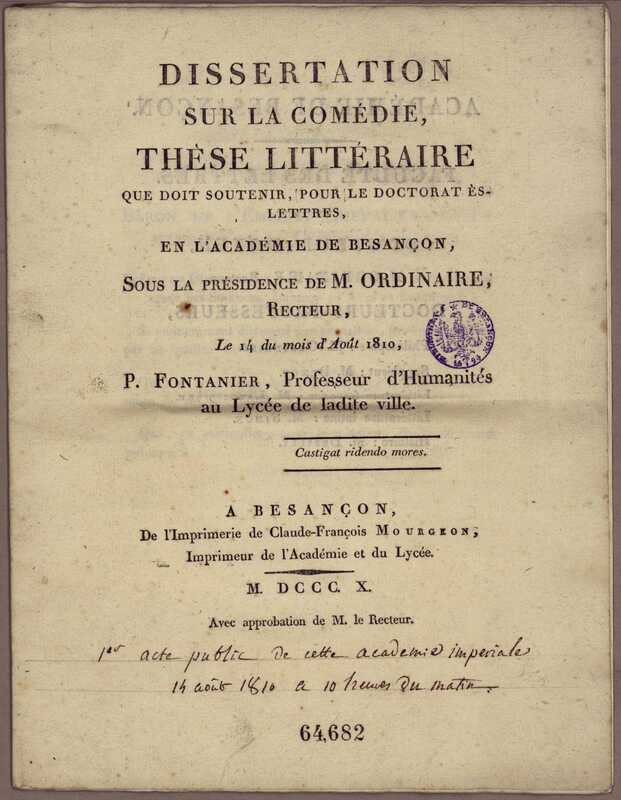

Pierre Fontanier was the first Doctor of Letters to publicly defend his theses: while 174 other Doctors received their title through conferral in 1810, this forty-year-old native of the Cantal region, a priest-turned-revolutionary who had become a lycée teacher and a respected family man [fig. 1], defended his positions on August 14 before the newly created Faculty of Letters in Besançon. For this erstwhile close associate of the “montagnards”, the aim was clear: to provide public and official assurances of his endorsement of the nascent regime, and to facilitate the collective forgetting of his past. These first two theses are brief: seven pages for the Latin thesis, De animâ humanâ [fig. 2], which addresses the substance of the soul and its faculties, and twelve pages for the French thesis, La Comédie, son origine, sa nature, ses différentes espèces, son influence sur les mœurs [fig. 3],which classifies comic plays according to genre, register, and other relevant criteria, and examines the tools used to write a comedy, with a particular focus on plot. In fact, those theses are simple programs, distributed to each member of the faculty at outset of the defense: the essence of the exercise is the oral performance of the candidate, who is required to“develop the theorems” of his theses – and not, as is the practice nowadays, summarize and recontextualize them – during a very formal ceremony, in front of the entire faculty [fig. 4]. The next two defenses took place in Paris, with André-Marie Ruinet (February 14, 1811) and Alexis Bintot (April 4, 1811), both directors of private boarding schools.

2. The time of the rhetorical theses: the example of Jules Michelet

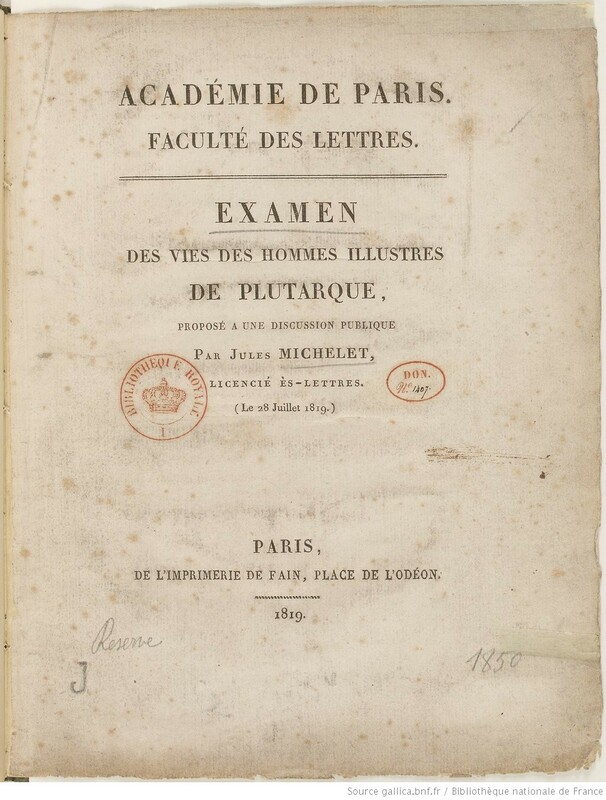

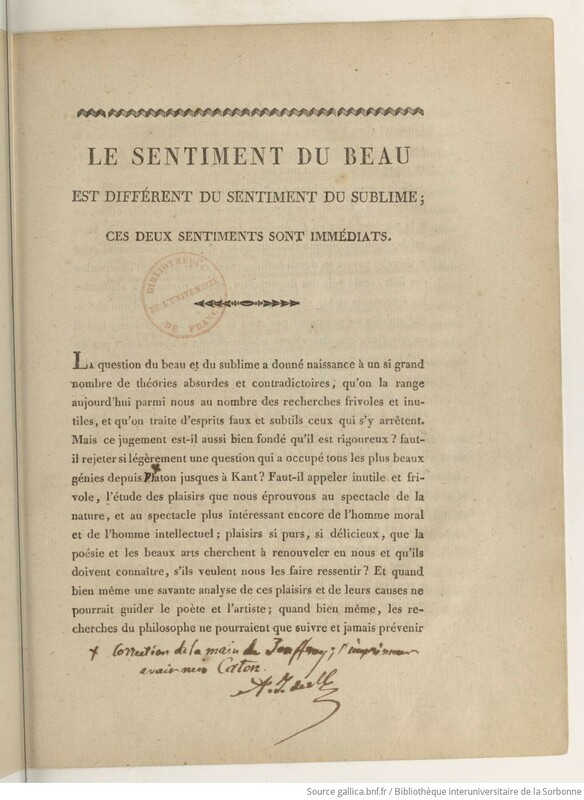

In the case of French theses, the hegemony of classical rhetoric and belles lettres was nearly absolute until the early 1830s. The subjects could be classified into three categories. Most often, as in the case of Pierre Fontanier, the thesis undertook a brief study of a literary genre (examples include De la satire, De la poésie pastorale, De l’épopée). This approach often involved a review of canonical authors – almost always Latin, Greek, or of the “Grand Siècle” era. The analysis presents a subjective evaluation of these authors’ works, highlighting both positive and negative aspects from the perspective of “good taste”. Another case in point: the thesis focuses on one of these authors (Homer, Sophocles, Tacitus) or one of his works (Le Petit carême de Massillon, Suetonius’ Life of the Twelve Caesars), again in order to judge above all, aesthetic and ethical qualities. This is the choice made by Jules Michelet in 1819 when he proposed Examen des Vies des hommes illustres de Plutarque, emphasizing above all the moral dimension and the style of this set of biographies [fig. 5]. Infrequently, and for those candidates most inclined to philosophical speculation, the subject could touch on pure aesthetics, for example, when Théodore Jouffroy defended his thesis entitled Le sentiment du beau est différent du sentiment du sublime ; ces deux sentiments sont immédiats (That the feeling of the beautiful is different from the feeling of the sublime; these two feelings are immediate), in 1816 [fig. 6]. The challenge for the candidate was to demonstrate that their cultural background and literary preferences aligned perfectly with the standards set by the University.

The Latin theses were no less varied, and similarly sought to guarantee knowledge of established tenets and doctrinal orthodoxy. The topic of the immortality of the soul was a common theme, as 8 out of 184 theses defended between 1810 and 1828 were entitled De Animae immortalitate or a small variation, like De immortalitate animae [fig. 7]. As popular a subject was liberty, as 8 out of 184 between 1810 and 1828 were entitled De libertate or a variation [fig. 8]. The prevailing approach was one of cautious generalities, with debate confined to the space between Condillac’s heirs – Laromiguière’s students at the Sorbonne – and the defenders of Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard’s spiritualism – Victor Cousin’s students at the École Normale.

3. Victor Cousin’s abandoned thesis

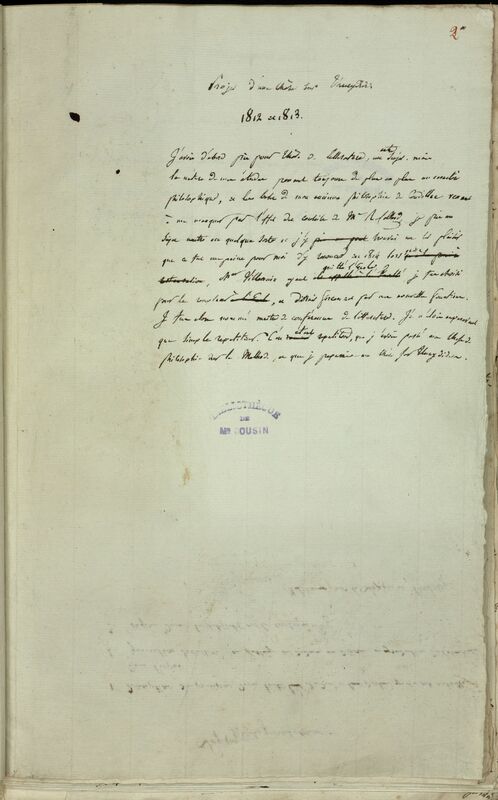

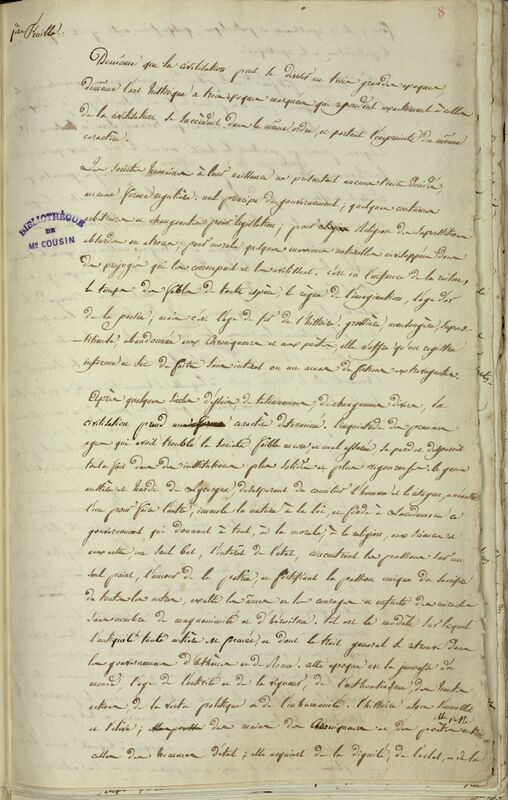

The preparation of these early theses has left few archival traces. However, it can be assumed that the investment of time and effort was not insignificant – at least more important than the brevity of the published texts alone would suggest, since it was a matter of preparing for a debate that theoretically involved the entire faculty. This is evidenced by the preparatory drafts, preserved in the Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne, of a thesis that was never defended: the French thesis that the young Victor Cousin intended to devote to Thucydides. On July 19, 1813, Cousin did indeed defend a Latin thesis in philosophy on Condillac’s analytical method (entitled De Methodo sive de analysi). However, the transformation of his philosophical conceptions, linked to his association with Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard, led him to choose as his French thesis a “somewhat neutral subject”, as he specified in the introductory note written many years later [fig. 9]. While neutral in the context of the debate between official philosophers, the thesis was in fact not neutral in itself. If the starting point of this text is a classical reflection on the writing of history as a reflection of the state of civilization [fig. 10], Cousin had to note that as “morality is linked to politics by the closest ties, all of Thucydides’ morality is in his politics”; Cousin therefore had no other choice than addressing political subjects, in his 111 pages of notes. An analysis of one of Athenagoras’ speeches (Book VI, ch. 39) reveals that he considered the Constitution of the United States to be a model of a “mixed government,” where the balance of power was achieved [fig. 12]. The draft conclusion takes an even more poetic turn, and Cousin’s identification with his author is evident: “For great historical monuments to be erected, great political events are necessary: these two things are inextricably linked. [...] Now this great event, necessary for the rise of a great historian, and this man capable of understanding this event and profiting from it, will soon appear. The Peloponnesian War is being prepared in silence, and Thucydides is already born.” In any case, the defense never took place, which Cousin justified by his appointment as lecturer of literature at the École Normale. However, it is also possible to posit that the invasion of France by the Coalition at the beginning of 1814, followed by the return of the monarchy, may have prompted the young academic to refrain from engaging in reflections that had become politically risky and to instead devote himself to more metaphysical inquiries.

4. The first foreign Doctors of Letters: in the wake of Stanislaw Rzewuski

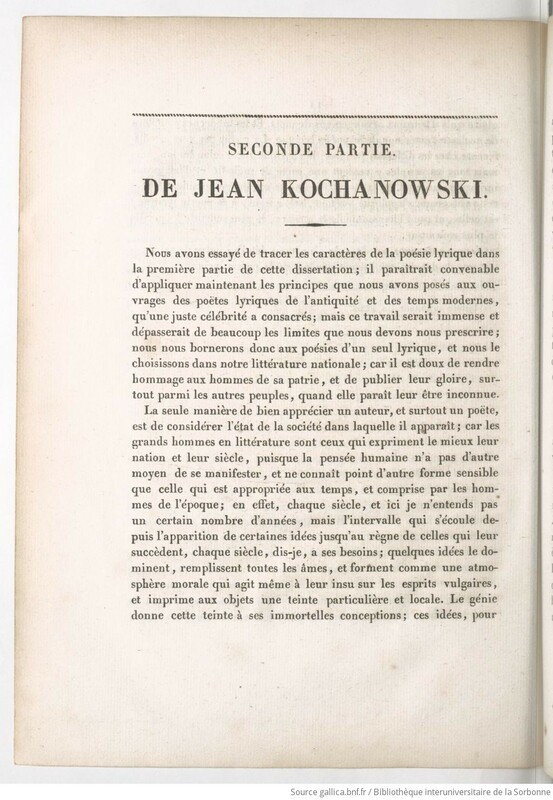

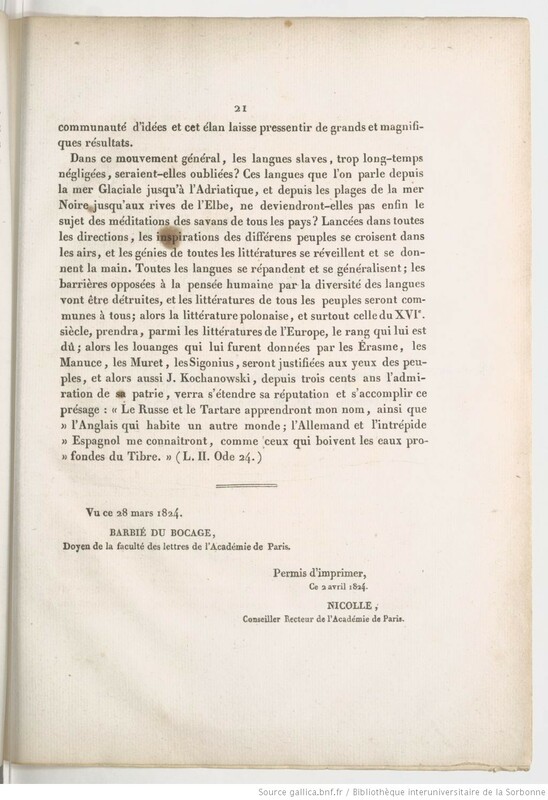

It must be noted that the Doctor of Letters attracted candidates who had, at an early stage, no professional ambitions. For example, Jean-Baptiste Félix Descuret, a doctor of medicine, defended his theses in 1818 without any intent to teach. Other cases are even more obvious, starting with foreign nationals who completed the entire curriculum, from the baccalaureate to the doctorate, before returning to their country. The first of these was the Polish nobleman Stanisław (Stanisław) Rzewuski [fig. 13], son of the renowned Orientalist Wacław Seweryn Rzewuski, who was nicknamed “Emir Rzewuski”. Raised in Vienna, the very young Stanislas defended on April 21, 1824, at the age of 18, at the conclusion of a three-year educational sojourn in Paris, a Latin thesis on a classical subject (De Ionica philosophia commentatio) and a French thesis entitled De la poésie lyrique et en particulier de Jean Kochanowski, lyrique polonais. The apologetic and nationalist intention is manifest: Rzewuski concludes that: “It’s so lovely to celebrate the men from our homeland and share their glory, especially among other nations, when it seems to be unknown to them.” [Fig. 14]. While Poland had been divided between Prussia, the Russian Empire and Austria since 1795, the defense of a doctorate in letters thus allowed Rzewuski to participate in the construction of this sixteenth-century humanist as a national writer, a means of ensuring that “Polish literature [...] [would] take the rank it deserves among the literatures of Europe” [fig. 15]. Rzewuski returned to Poland, where he became an artillery officer, took part in the November Uprising against Russian tutelage, and died in 1831. However, the torch was taken up from 1832 onwards by his compatriot Adam Mickiewicz, who would laud Kochanowski in his lectures at the Collège de France, where he was elected in 1840.

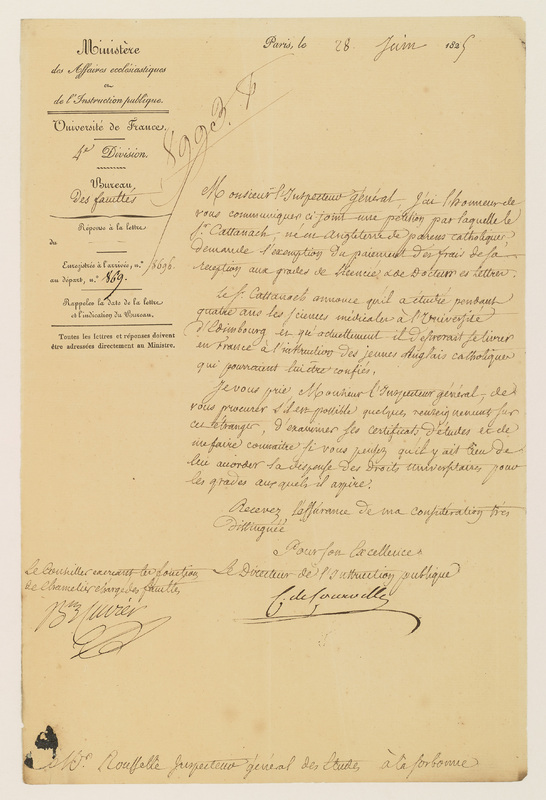

The following year, 1825, the Englishman John Cattanach of Alnwick obtained his doctorate at the age of 34: due to his Catholic faith, he could not study in English universities, despite his aspiration to become a teacher. The project he presented to the Grand Master, the Bishop of Hermopolis, Denis Frayssinous, to obtain a waiver of fees and an exemption from the French thesis, was well thought-out: “It is only the degree of Doctor that would afford me sufficient consideration to be entrusted with the pupils I would bring back to France to educate them. It is my intention to commence my career as a private tutor, with the aspiration of one day establishing a pension in Paris for my fellow countrymen and women, particularly those of the British Catholic faith”. With the support of the Royal Council of Public Instruction, Cattanach received both the requested waiver of examination and seal fees and, uniquely, permission to limit himself to one Latin dissertation, De beatitudine. In 1827, the Dutchman Antonius Alexius Josephus Meylink received the title, at the age of 30, after a two-year stay in Paris. He returned to the Netherlands the same year, pursued legal studies in Ghent and Leiden, and subsequently became a prominent member of the bourgeoisie, a renowned lawyer in The Hague, and eventually a parliamentarian.

5. Academic innovations in the 1830s: Henri Monin and Edward Barry

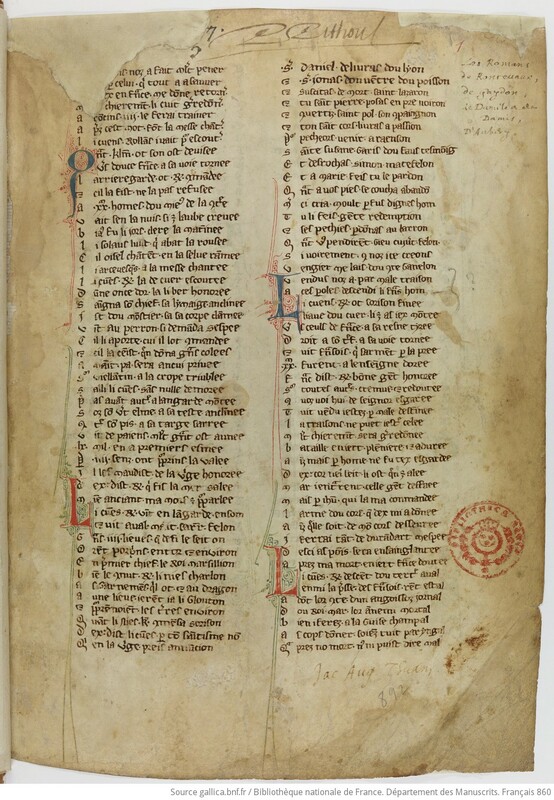

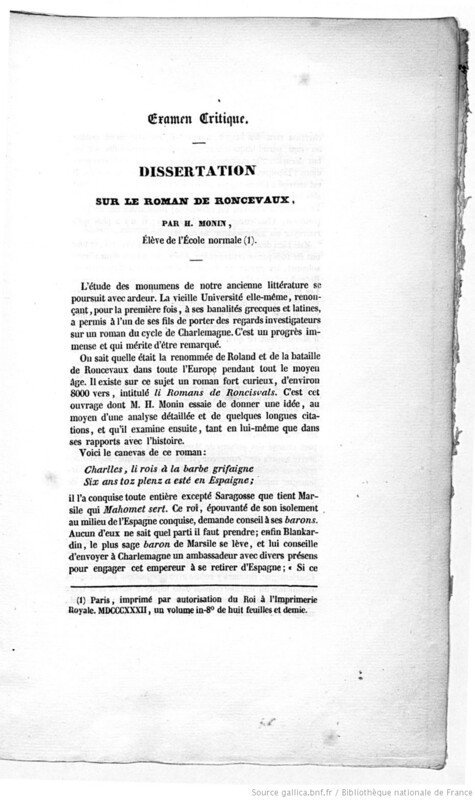

The early 1830s saw the gradual emancipation of dissertations from the disciplinary framework that had been imposed by the First Empire. The lack of specificity in the Napoleonic decrees regarding the scope of “philosophy” and “ancient and modern literature” allowed for a diversification of subjects, particularly considering the evolving liberal context. In particular, the creation of the agrégation in history and geography in 1831, in addition to the agrégations in philosophy, literature and grammar, fostered the emergence of historical French theses. Louis-Henri Monin was thus the first to base his thesis on original and then unpublished manuscripts kept in the Bibliothèque royale (MSS 7227/5 [fig. 17] and 254/21). He proposed the first analysis of Chanson de Rolland, based on the partial edition of a text hitherto considered lost. Monin was particularly interested in determining whether this was a standalone literary work or a poem that was gradually formed from popular traditions. Francisque Michel, in a widely circulated magazine, Le Cabinet de lecture, congratulated “the old University” for having “for the first time renounced its Greek and Latin banalities” by allowing “one of its sons to take an investigative look at a novel from the Charlemagne cycle” [Fig. 15]. Indeed, the publication of this thesis by the Imprimerie royale shows the official endorsement given to these new practices. Barry’s dissertation [fig. 20], dedicated to the Robin Hood cycle and defended in the same year, did not use unpublished sources, but it was nevertheless concerned with related issues, focusing on popular literature, more precisely on the transformations of the same theme “in the different periods of the poetic life of a people”. The break that opened up then also included the thesis of Jules-Augustin Fleury, Des Pelasges, which was interested in the first settlements of Greece, or that of Henri Wallon, Du droit d’asyle, in 1837, devoted to the history of the right of asylum from antiquity, in particular its defense by the Church until its abolition by Francis I. One could add theses focusing on Merovingian and Carolingian questions, such as Julien-Marie Lehuërou and his thesis, De l’établissement des Francs dans la Gaule et du gouvernement des premiers Mérovingiens jusqu’à la mort de Brunehaut, or Pierre-Joseph Varin, with De l’influence des questions de races sous les derniers Karolingiens. This trend was part of a broader cultural conjuncture: the Romantic movement played an important role in the rehabilitation of the Middle Ages, considered the heroic period par excellence, and the place of national origins.

Philosophy followed the same path a little later, with the defense of theses on philosophical subjects in French - and not Latin – that were not aligned with the conventional academic discourse. One notable example is Pierre-Benjamin Lafaist (or Lafaye), who adopted an historical perspective with Sur la philosophie atomistique, defended in 1833 (and also published by the Imprimerie royale). This thesis attempted to reconstruct the system of Leucippus and Democritus in order to compare it with the Eleatic school - without endorsing it, but concluding that “they have deserved well from science”. Charles Bénard followed the same perspective, adopted a similar approach, but with a thesis concerning theories that were current at the time. He wrote a Dissertation sur la théorie des forces fondamentales dans le système de Gall et de Spurzheim, that is to say, on phrenology, from which it was a question of isolating the fundamental principles [Fig. 21]. Some authors were bold enough to put forth new conceptual proposals. Antoine Charma in Caen in 1831, for instance, presented his Essai sur le langage. However, the most notable contribution in this regard was Félix Ravaisson’s 1837 thesis entitled De l’habitude, which was widely celebrated and quickly became famous. This trajectory was subsequently pursued by Francisque Bouillier in his 1839 thesis, Sur la légitimité de la faculté de connaître, and by Edgar Quinet in his 1839 treatise, Considérations philosophiques sur l’art.

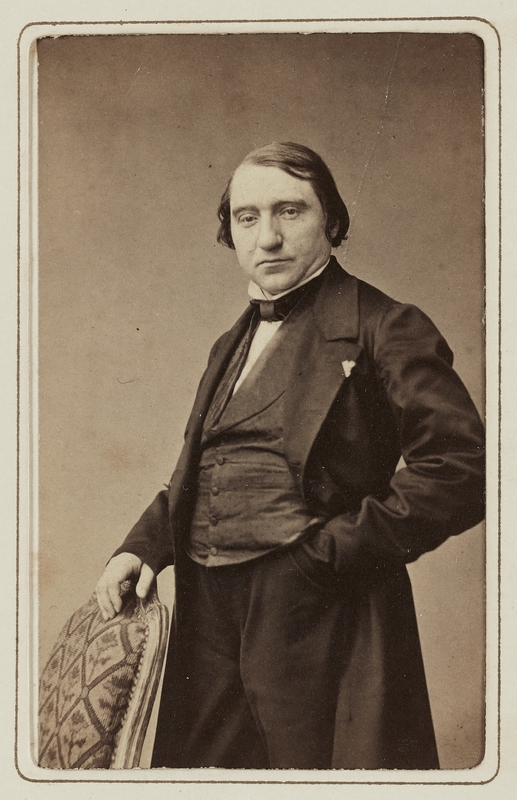

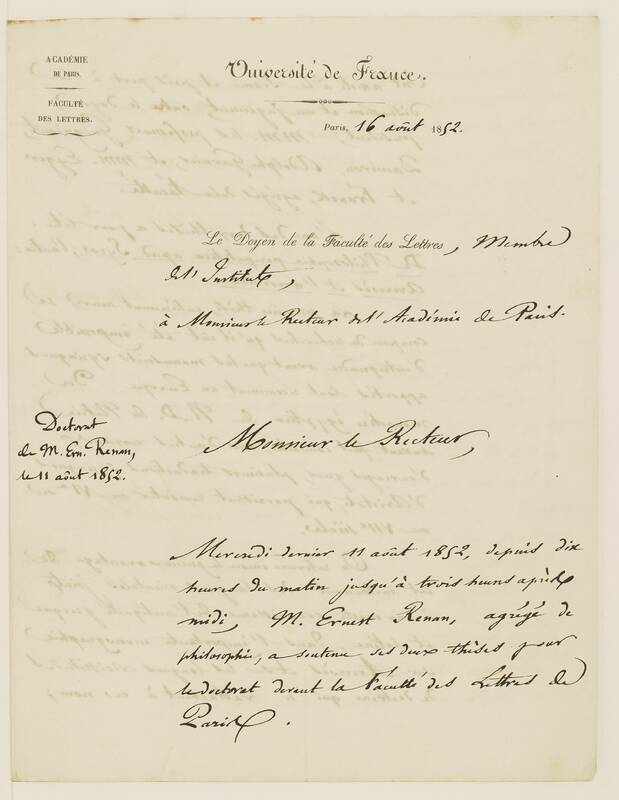

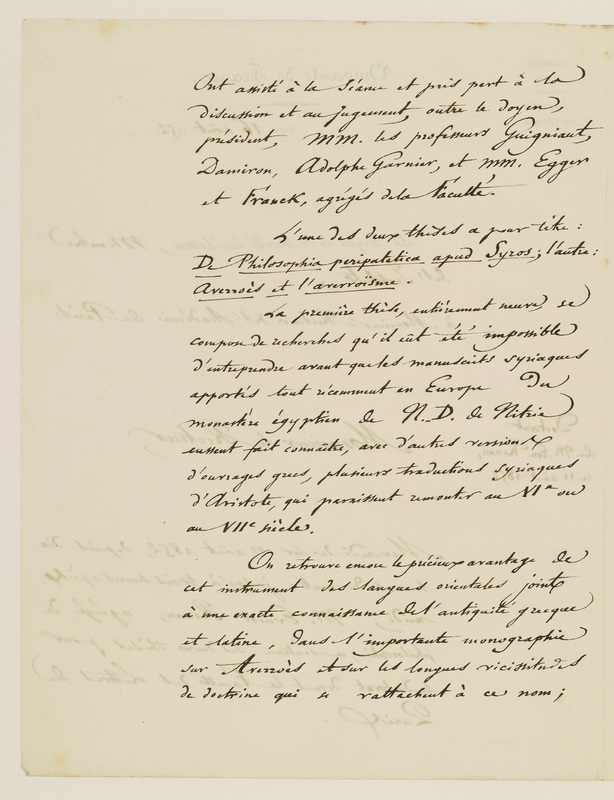

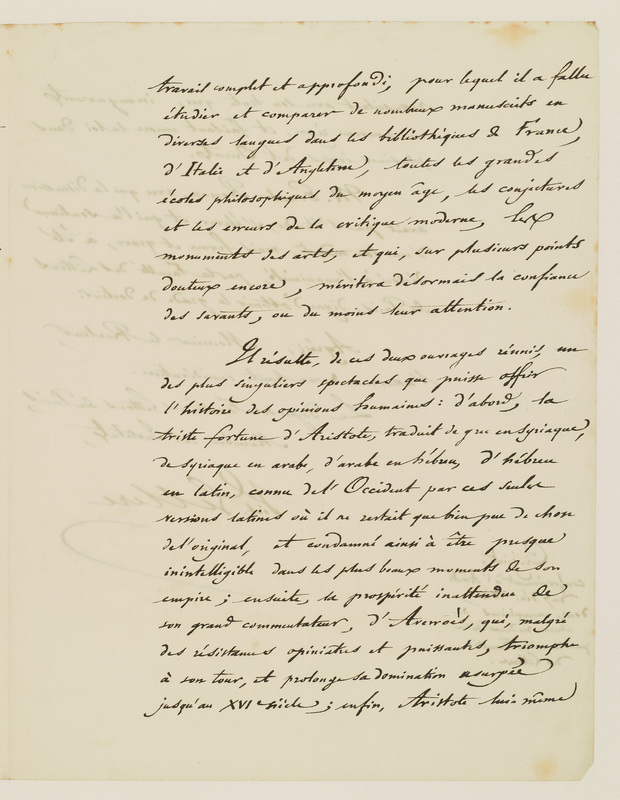

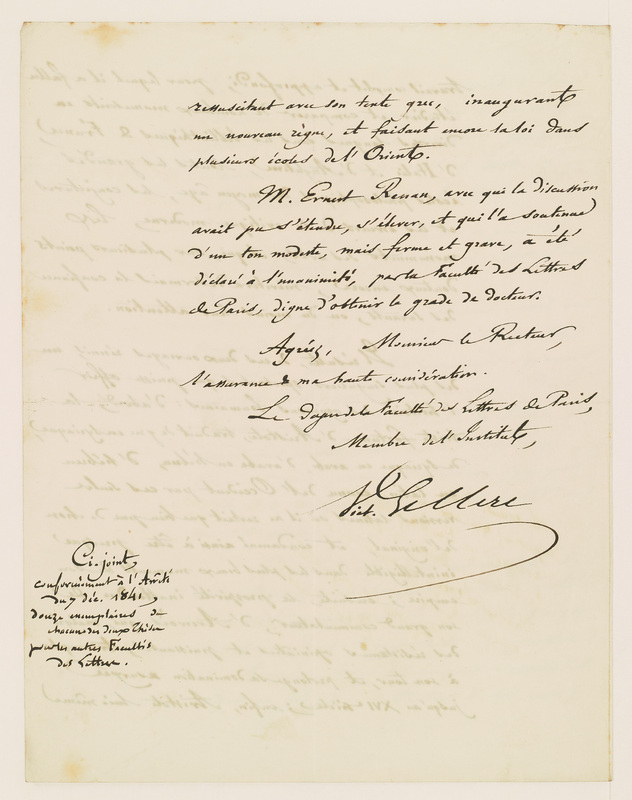

6. Journey to the East: Ernest Renan

In the wake of the innovations of the 1830s, ratified in 1840 by the regulations that allowed each candidate to choose the subject of his research “according to the nature of his studies and among the objects of the faculty’s teaching”, there was a proliferation of theses devoted to subjects at the frontiers of classical culture – the freedom offered to candidates was in fact tempered by the range of potential career paths. We can take as an example the work of the young Ernest Renan [fig. 24], whose hesitations can be followed thanks to his correspondence with his sister Henriette. In 1847, already engaged in the study of Oriental languages, he presented himself to the dean of the Sorbonne Joseph-Victor Le Clerc, with whom he defined subjects according to three criteria: “1° [...] to take a subject in the field of [his] Oriental studies”, since he was then beginning the study of Sanskrit and Persian, following his previous study of Hebrew, Syriac, and Arabic; “2° to make it accessible to the faculty, whose focus is exclusively on classical studies, and thus to situate it at the intersection between the Orient and Greece; 3° not to shock orthodoxy too openly.” [Fig. 25 and 26]. He was more cautious than the dean as he was convinced of the “absolute necessity to avoid any contact with theological susceptibilities”. Finally, Renan decided to propose a comprehensive and transversal French thesis, to be entitled Histoire des études grecques chez les peuples orientaux, and a Latin thesis on Averroes, in accordance with the standards of a history of erudite philosophy as defended by Victor Cousin at the time. But the defense did not take place until five years later, on August 11, 1852, which illustrates the elevated standards that candidates for university careers were already expected to meet. In the meantime, the work on Averroës and Averroism had developed to such an extent that it had become the subject of the French thesis: by doing so, Renan positioned himself even more as a scholar, rather than a rhetorician in the now old-fashioned manner. Indeed, in his report the dean praised a “thorough and comprehensive work, for which it was essential to examine and compare a multitude of manuscripts in diverse languages” – Renan benefited in particular from an eight-month mission to Italy in 1849-1850. Similarly, L’Histoire des études grecques chez les peuples orientaux was replaced by a Latin dissertation, De Philosophia peripatetica apud Syros, based on the Syriac manuscripts of the Monastery “of the Syrians”, or Deir al-Surian, in the Nitrian Desert, acquired by the British Museum between 1839 and 1851 – and which Renan was able to study in 1851, thanks to funding from the Ministry of Public Instruction.

Fig. 27: Report by Dean Victor Leclerc on the defense of Ernest Renan. August 16, 1852. Archives nationales, F/17/4660

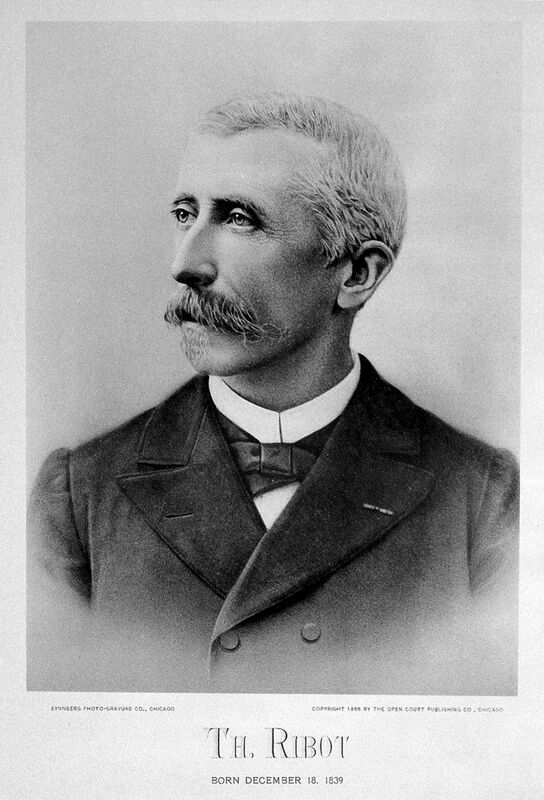

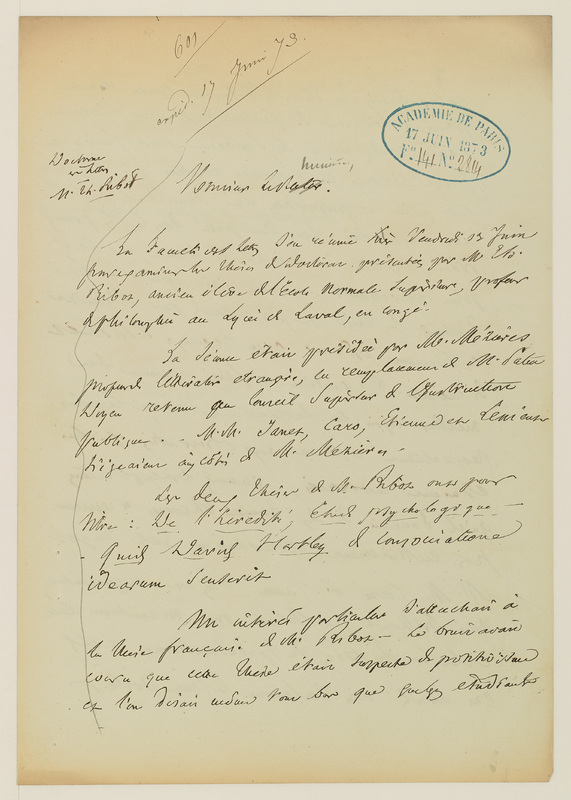

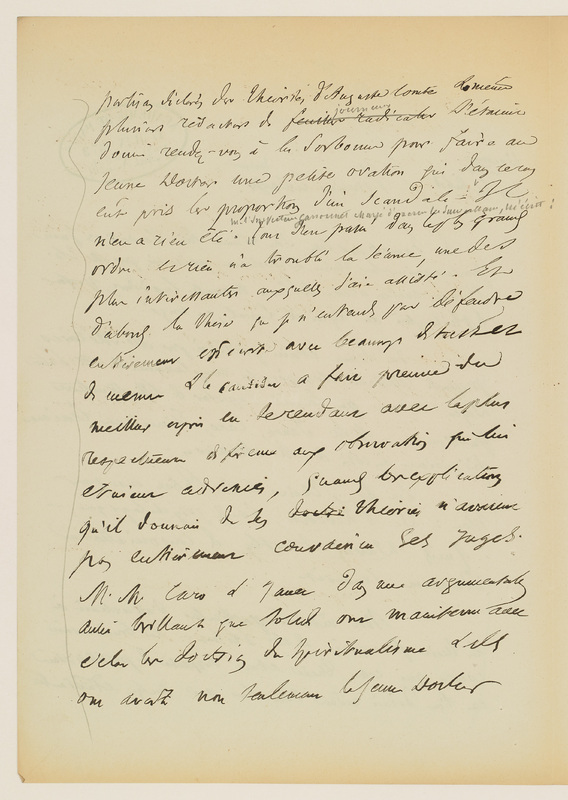

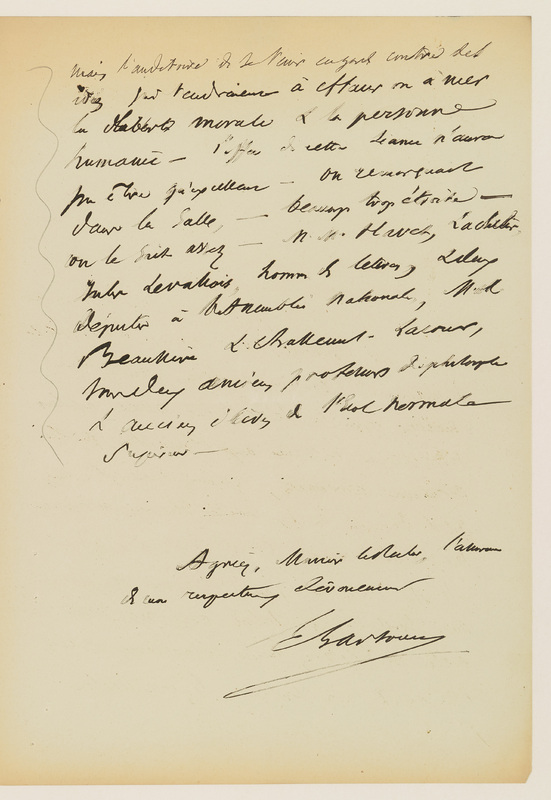

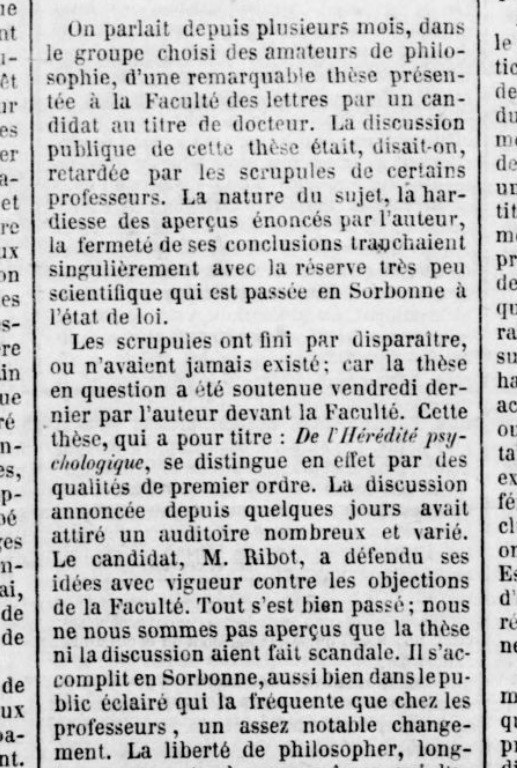

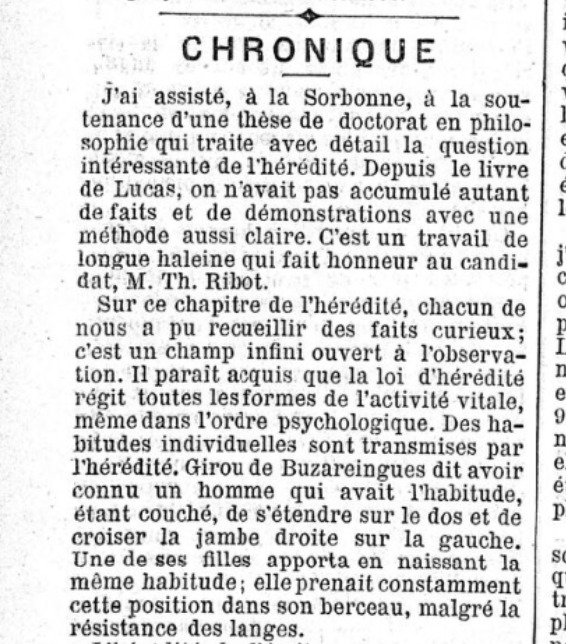

7. “Defend” experimental psychology: Théodule Ribot

From the 1850s and 1860s onwards, doctoral theses assumed a significant role in intellectual discourse, to the extent that their defenses became public events that were sometimes very popular, serving as a platform for the most current debates. As the imperative of novelty became stronger and stronger, theses became relevant indicators for monitoring the introduction of new intellectual trends in the university environment. One illustrative example is the French thesis presented in June 1873 by Théodule Ribot [fig. 28] on L’Hérédité : étude psychologique sur ses phénomènes, ses lois, ses causes, ses conséquences. This thesis was “suspected of positivism” even before the defense, which gave rise to fears that students “declared partisans of the theories of Auguste Comte” had “arranged to meet at the Sorbonne to give the young doctor a small ovation, which in this case would have taken on the proportions of a scandal” (defense report, Archives nationales, AJ/161/356). If this was not the case, the debate between Ribot, a practitioner of experimental psychology, and his judges Elme Caro and Paul Janet, heirs of Victor Cousin and supporters of spiritualism, nevertheless filled the Salle des Actes of the Sorbonne with spectators, attracting students, scholars, journalists and politicians. The press also provided coverage of the event, as evidenced by articles in La République française of June 18 [fig. 30] or Le Temps of June 20, 1873 [fig. 31]. Ribot’s thesis was in opposition to the prevailing views held by the academic community at the time: he put forth the notion that the biological law of heredity was applicable not only to physiological phenomena, but also to mental phenomena. Furthermore, he advocated for a shift in psychological methodology, emphasizing the primacy of empirical and experimental approaches over those based on introspection. As a result of his contributions, he was appointed to a chair of “experimental and comparative psychology” at the Collège de France in 1888. After him, other theses of “experimental philosophy” were defended, laying the groundwork for the affirmation of psychology as a distinct discipline. This included the work of Alfred Espinas on Sociétés animales (1877), which sought to establish a “comparative psychology” between humans and other animals, Victor Egger who defended what he called “descriptive psychology” with La parole intérieure (1881), and Pierre Janet on L’automatisme psychologique (1889), which was intended to be an “essay in experimental psychology”.

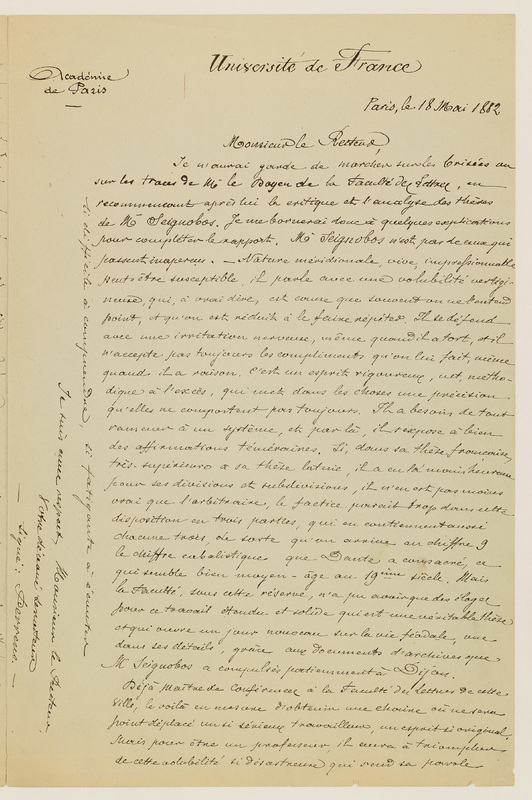

8. “This disastrous volubility”: Charles Seignobos

While innovation and scientific rigour were of great importance in the evaluation of doctoral theses, it would be erroneous to assume that the institution was disinterested in the interpersonal skills of the candidates. On the contrary, the reports written by deans and inspectors utilized the defense as an occasion to provide a comprehensive account of the future doctor’s character, encompassing not only intellectual attributes but also physical and moral qualities. These descriptions were subsequently considered by the ministerial administration in the regulation of careers.

We can take as an example the report written by Inspector François-Tommy Perrens about the defense of Charles Seignobos, a former student of the École normale supérieure, who was ranked first in the agrégation in history in 1877. Seignobos returned to France after spending two years in Germany thanks to a scholarship, between 1877 and 1879, and defended his two theses, De indole plebis Romanae apud Titum Livium and Le régime féodal en Bourgogne jusqu’en 1360, on April 29, 1882. He was then teaching history at the Faculty of Letters in Dijon for three years: the unofficial mission that had been entrusted to him by the ministry (which on this occasion used a new statute, since the maîtres de conferences of the faculties appeared in 1877) was to try to acclimatize the seminar-based way of teaching that he had been able to observe in Germany, in a faculty outside Paris – and therefore without the support of the École pratique des Hautes études, confined to a floor of the Sorbonne. In addition to the dean, Auguste Himly, the jury included Numa-Denis Fustel de Coulanges, Ernest Lavisse, Henri Pigeonneau, Alfred Rambaud, Jules Zeller, and Alexandre Beljame, the first professor of English languages and literatures at the Faculty of Letters (which is undoubtedly explained by the subject and the period of the thesis, which is linked to the Hundred Years’ War and thus to the British presence in France). The dean’s report seems to be particularly harsh both on the content of the two theses and on the candidate’s oratorical qualities. Inspector Perrens was even more precise: “Of a southern nature, lively, impressionable, and perhaps somewhat sensitive, he speaks with a dizzy volubility which, to tell the truth, often prevents us from fully comprehending his ideas and forces us to rely on repetition”. However, Perrens added: “He is a rigorous, clear, methodical mind, perhaps to a fault, which imposes a precision that the subject matter may not always warrant”. Notwithstanding the deficiencies in his expression and the harsh criticism of his Latin thesis, Seignobos received “the mention of unanimity”, i.e. the highest commendation: the qualities of his work, in coherence with the ministerial policy of support for scholarly research, outweighed its shortcomings. His dedication and seriousness of purpose were viewed as compensating factors for his “disastrous volubility”.