A material history of doctoral theses

1. From placards to in-octavos

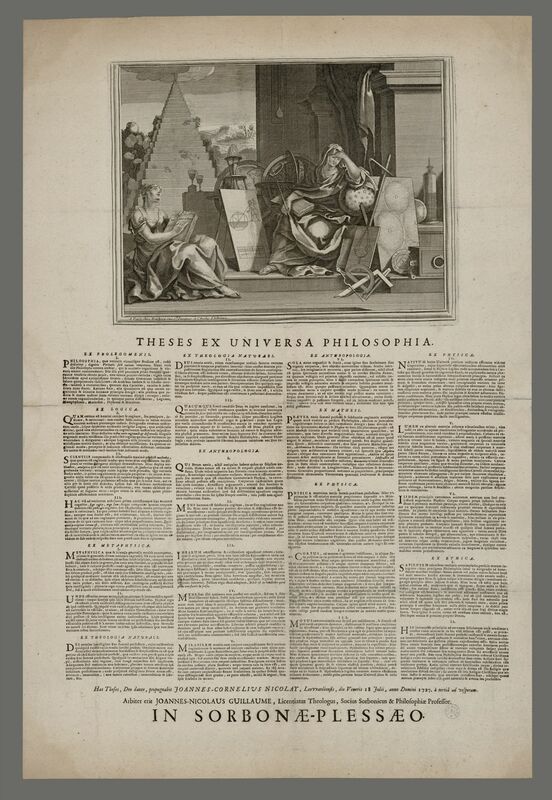

Under the Ancien Régime, doctoral theses served two primary functions. First, they functioned as public notices, informing the general public about the scheduled defenses. Second, they served as souvenirs, which new graduates often distributed freely. These documents were typically limited to a single page, with the majority being large folios featuring engraved frontispieces. These frontispieces were occasionally elaborate, showcasing the list of proposals developed and defended orally by the candidate [fig. 1].

2. The thesis publishing market

The reestablishment of a system of higher education by the First Empire did not completely negate these initial functions. For example, while engravings disappeared, a few very rare theses were still in folio, such as the lost one that André-Marie Ruinet defended in philosophy in Paris in 1811. Nevertheless, the in-4° format, although legally imposed solely on doctorates in medicine (by article 20 of the decree of 20 Prairial, year XI), was by far the most common between 1810 and 1820. In this intermediate period, all the evidence suggests theses were still displayed sometimes on walls or doors and, more notably, that they were distributed as booklets, serving as a brief program or prospectus for the defense, typically provided to the jury at the outset of the session. This practice is exemplified by the very first defense of a doctoratèslettres, that of Pierre Fontanier. Probably appearing in Caen in 1829 with the theses of François-Gabriel Bertrand, the in-8° format became commonplace in the 1830s, without the intervention of a regulatory text. This change in format reflects the evolution of the function of these documents and, more generally, the transition from an oral to a written tradition in what constitutes the essence of university excellence. From mere accessories to the defense, the theses became the primary focus, intended to be read independently, as standalone works. Some even received a second edition, beginning with the one defended by Antoine Charma in Caen in 1831, entitled Essai sur le langage, which was subsequently republished by Hachette in 1846.

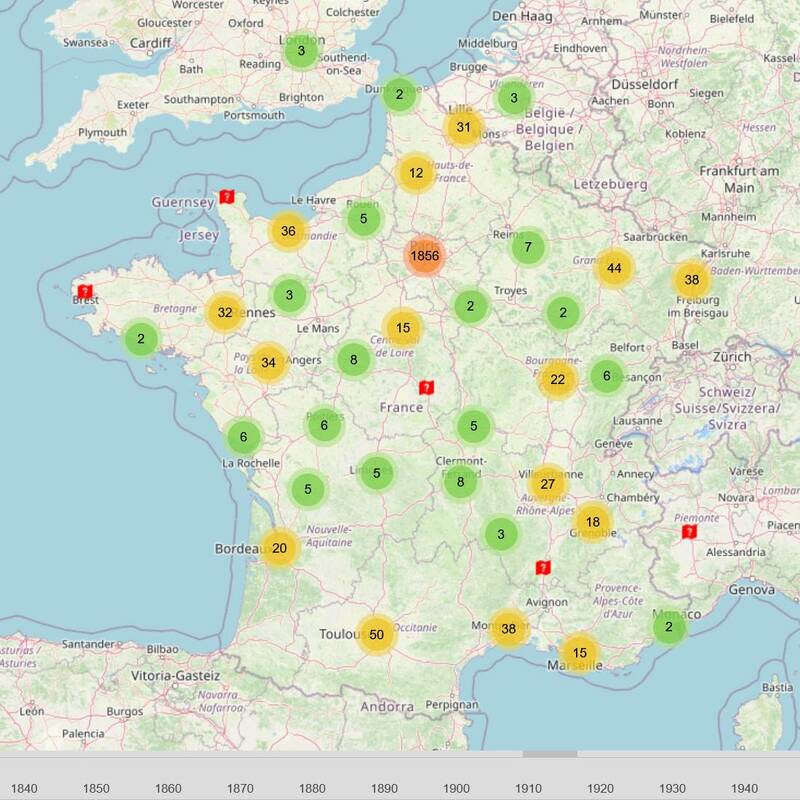

A very specific and relatively obscure publishing sector emerged, that of doctoral theses. Since theses had to be printed in order to be defended, the doctoral candidate had no choice but to find a professional printer and publisher, at his own expense – although the Ministry of Public Instruction was quick to set up mechanisms for reimbursing the costs, always on condition that the defense was a resounding success. The very first Parisian theses generally seem to have come out of the presses of Armand-Louis-Jean Fain, printer of the Université impériale, and Charles-Frobert Patris, but the market diversified greatly from the mid-1820s onwards. Very few were those who, like Henri Monin in 1832, benefited from the full support of the Imprimerie royale. Most often, candidates turned to a variety of small printers – unless the chosen subject required the use of Greek characters, which were not common. Although the current state of research does not allow for definitive conclusions to be drawn, it seems that a period of dispersion, which lasted at least from the 1820s to the 1840s, occurred when only Firmin Didot and Joubert seem to have printed theses on a regular basis (up to four or five per year in the 1840s). This was followed by a period of concentration in doctoral publishing. The largest publisher of dissertations over the entire nineteenth century was clearly Louis Hachette, with at least 220 volumes. Although this publisher, who founded his company in 1826 and for a long time devoted himself exclusively to school and university publishing, did not begin to publish this type of work until 1847 – with a notable increase in activity from the 1870s onwards. The second most active publisher was Ernest Thorin, who entered the market in 1866 and published more than 150 titles, followed by Adolphe-Auguste Durand, who published nearly a hundred theses for an activity that began in 1848, and by the very dynamic Félix Alcan, who did not enter the market until 1884 but published 61 dissertations between 1884 and 1899. The fact remains that the market was undoubtedly open: the mapping of the publishing sites made possible by the database created by the Projet ès lettres [Fig. 2] demonstrates that while 1776 theses out of 2382 (i.e., 74%) are published in Paris, which is to be expected given the country’s centralization, whether in the academic or publishing fields, the dominance is not absolute. In the nineteenth century, Publishers in Toulouse published 41 theses, 39 in Nancy, 36 in Strasbourg, 32 in Caen. It is notable that a significant proportion of candidates employed professionals from non-university cities, who were undoubtedly less financially demanding, like Châlons-en-Champagne or Amiens. However, others went as far as sending their manuscript to publishers in London or Brussels.