The institutional framework of the Doctor of Letters in the 19th century

The First Empire underwent a complete reorganization of the French higher education system, through the enactment of the law of May 10, 1806, and the subsequent decree of March 17, 1808. The Napoleonic government established a system of higher education based on degrees and their conferral, in order to transform degrees from mere markers of social and ideological conformity, or institutional rites of passage, into certificates of competence that organised professional careers –in law, medicine, theology and education. The ultimate goal was to establish a novel corporation, a unified university structure organized according to talent and merit, necessitating a systematic and standardized approach to differentiating individual trajectories. The highest of these degrees was the doctorate, then an innovation for the humanities and sciences: in the old faculties of arts, the highest degree was the master’s degree, while the doctorate was reserved for the faculties of theology, law and medicine. From the perspective of the legislator, the new title, awarded by the just as new facultés des lettres and facultés des sciences, was designed to serve two distinct functions: firstly, as a barrier to entry, and secondly, as a level of qualification, that would regulate access to the pinnacle of the teaching profession.

For the humanities, the doctorate was primarily designed to showcase a particular rhetorical and argumentative proficiency, along with a comprehensive grasp of established knowledge and teaching practices. The Statute of the Faculties of Letters and Sciences of February 16, 1810, stipulated that each candidate had to defend two theses: one in Latin on “Philosophy” and the other in French on “Ancient and Modern Literature”. In the beginning, these theses assumed the form of brief programmatic texts, announcing the arguments to be developed orally, rarely exceeding twenty pages. In any case, since the purpose of the doctorate was to certify excellence in the art of teaching –and only this– the legislator considered that it could be granted automatically, without theses or defence, to those who were already occupying the positions to which it was a prerequisite –the same rule applied to the two previous degrees, the baccalauréat and the licence.

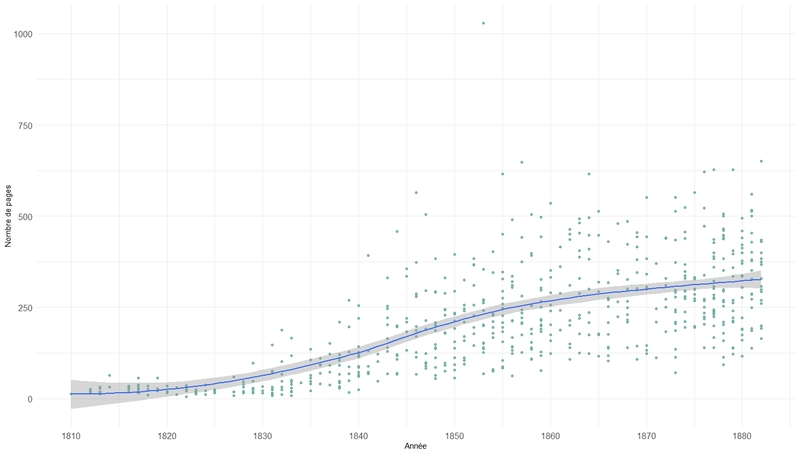

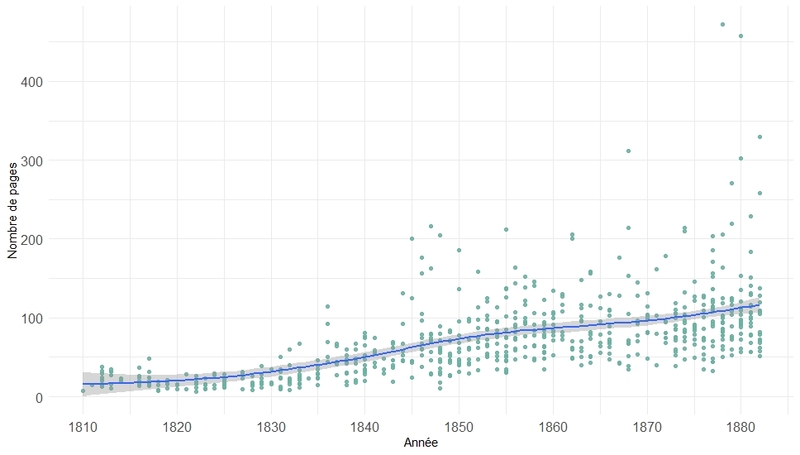

This system was abolished in 1831, thereby rendering the defense an unavoidable requirement for those who aspired to the doctorate. At the same time, however, academics demonstrated an increasing demand for rigor and depth in doctoral studies. This is evidenced by a gradual yet consistent expansion in the length of theses from the 1830s onwards, as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. [Figs. 1 and 2]. It was then that the first erudite theses appeared, guided by the mentorship of prominent professors. The diversification of thesis subjects and the beginnings of the quest for novelty and originality received subsequent official recognition when Victor Cousin, himself a professor at the Faculty of Letters in Paris, became Minister of Public Instruction. As a matter of fact Cousin’s tenure, which spanned from March to October 1840, saw a significant transformation in the regulatory requirements, as outlined in the Royal Council’s decree of July 17, 1840. If the Latin and French theses continued to exist, they were no longer constrained by disciplinary boundaries, as the candidate had to choose his subjects “according to the nature of his studies and among the subjects taught by the faculty”. This decree remained the overarching framework throughout the Second Empire and to the beginning of the Third Republic, promoting progressive disciplinary specialization.

The Third Republic’s action on the doctorate was strong, but not immediately apparent, at least initially. The Ministry of Public Instruction obtained the creation of doctoral scholarships for a period of two years (without extension) by the decree of November 5, 1877. These scholarships were intended to increase the number of candidates for the degree. The implementation of this first system of student funding coincided with the creation of a junior status (maître de conferences, comparable to a lecturer or assistant professor), which offered new professional opportunities to doctoral candidates. In these two respects, the doctorate thus constituted a significant instrument of action for the Republican government in its policy of developing and modernizing higher education: the defeat at the hands of Germany in 1871 was attributed in part to the weakness of the learned elite of the Second Empire. As the doctorateassumed an increasingly pivotal role in professional advancement, theses became more and more erudite, exhaustive, and ambitious – requiring more and more years of labour. In 1897, a second type of doctorate was created with the objective of attracting foreign students: the “university” doctorate (doctorat d’université)– to differentiate it from the “State” doctorate. This diploma was more accessible than the first type because it did not require prior possession of a licencedegree or a baccalaureate, reducing the number of years required. Even more, it could be awarded honoris causa, which demonstrates the extent to which the aura of the doctorate had then transcended its original professional function.

The July 28, 1903 decree signified the pinnacle of this new symbolic status of the thesis and the doctorate, as it introduced sweeping changes to the requirements for the degree. The obligation to defend a thesis in Latin disappeared in the name of the modern scientific character acquired by the doctoral degree. If nothing has changed for the first thesis, the Ministry reminded the prospective candidates and the professorsthat, in the administration’s eyes, “the thesis is generally the first important scientific work of a young professor; it is not necessary, and it is even dangerous, for him to start with a book of too great a scale and to spend too many years on it”. In this way, this circular(an internal administrative instruction)demonstrates that the administration was already concerned about the significant increase in the number of thesespages, despite its inability to intervene and reverse this fundamental trend.